Welcome to — a newsletter dedicated to exploring the world and our place in it. For the full map of posts, see here.

Today’s post is written by , author of — an excellent newsletter that delves into the lesser known parts of ancient history.

In 1177 BC, Ammurapi, the last king of Ugarit, a port city in Northern Syria sent a frantic cry for help. The letter addressed to the ruler of Alashiya, a kingdom in Cyprus, said:

My father, behold, the enemy’s ships came; my cities were burned, and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots are in the Land of Hatti, and all my ships are in the Land of Lukka? Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: the seven ships of the enemy that came here inflicted much damage upon us.

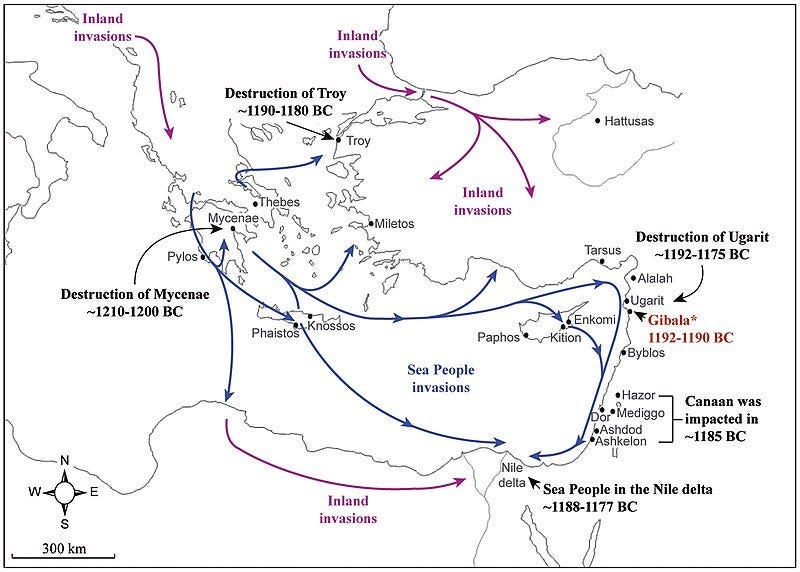

The message never reached its destination. Ugarit, a great Bronze Age metropolis, was destroyed, and its inhabitants massacred. Ugarit wasn’t the only one.

During the late Bronze Age, cities in the Middle East, North Africa, and the Mediterranean fell apart. Highly developed societies collapsed and never recovered. We call this series of unfortunate events the Bronze Age Collapse.

Who could have possibly caused such mindless destruction?

The Sea Peoples, a roving band of mariners, were found guilty! They staged a large-scale amphibious assault on thriving cities of the Bronze Age. They came from the sea, destroyed, burned, killed, looted, and vanished!

Or did they? Could a disorganized band of pirates bring down mighty civilizations? We don’t have a straightforward answer, but using historical evidence we can try to figure out who they were and what motivated them to attack the major powers in the Near East.

In this post we’ll explore the origins of the Sea Peoples and discuss all the ancient sources that mention them. We’ll also cover every group of Sea Peoples mentioned in the records. But before we review the historical texts, have you ever wondered why they were called the “Sea Peoples”?

Why “Sea Peoples”?

French Egyptologist Emmanuel de Rougé coined the term “Sea Peoples” or “people of the sea” in the 19th century while describing inscriptions of Pharaoh Ramses III in his book Note on Some Hieroglyphic Texts Recently Published by Mr. Greene.

Rougé put together his ideas and published his research as the Excerpts of a dissertation on the attacks directed against Egypt by the peoples of the Mediterranean in the 14th century BC. He was later appointed as the chair of Egyptology at Collège de France. His successor Gaston Maspero popularized the term “Sea Peoples” and the associated invasion theory through his work The Struggle of the Nations, published in 1895.

The story of barbaric invaders inflicting devastation on peaceful, settled communities has fascinated the human imagination for as long as we can remember. But the truth is complex.

It’s possible that the Sea Peoples’ sudden arrival from the sea and destruction of cities wasn’t as unexpected as is commonly believed. Nor did they vanish into the sea after pillaging. Let’s examine primary sources about them and then discuss some popular theories about their identities.

Primary sources from the ancient world

The Sea Peoples are not an ethnic group but a confederation of people from different lands.

Their earliest mention comes from the Abishemu Obelisk (dated 2000 BC to 1700 BC). The inscription talks about Kukkunis, the son of Lukka. The Kukkunis, or Caucones, were an Anatolian tribe based in the kingdom of Lukka, located in Western Anatolia. Lukka is one of the Sea Peoples we’ll encounter throughout ancient sources.

The next mention of the Sea Peoples is from the Amarna letters, written in the mid-14th century BC. These letters were a series of correspondences between the Egyptian pharaohs and the rulers of the Aegean, Canaan, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia. Denyen, Lukka, and Sherden are mentioned in the Amarna letters and were among several groups of Sea Peoples.

Our next source comes from Pharaoh Ramesses II’s inscriptions about his famous clash at Kadesh in 1274 BC against the Hittites. Ramesses says the Hittites had Lukka soldiers in their confederation, while the Egyptians had Sherden mercenaries among their forces.

Ramesses II’s successor and son, Pharaoh Merneptah, made the first clear mention of a sea invasion in 1207 BC. In the Great Karnak Inscription, Arthibis Stele, and the Israel Stele, Merneptah talks about the Libyan King Meryey, who allied with several groups of Sea Peoples and attacked the Nile Delta. Merneptah defeated this invading coalition after a six-hour battle. The Sea Peoples in the Libyan force included Ekwesh, Teresh, Lukka, Sherden, and Sheklesh.

Our next, and perhaps the most famous and detailed source about the Sea Peoples, is Pharaoh Ramesses III’s mortuary temple, the Medinet Habu. The inscription describes a “coalition of the sea” that invaded Egypt. An epic clash occurred between the Egyptians and the Sea Peoples around 1175 BC, resulting in a decisive Egyptian victory. The invading confederation included the Pelest, Tjekker, Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh.

Ramesses III describes how the Sea Peoples laid waste to civilizations of the Near East:

The foreign countries [i.e. Sea Peoples] made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms: from Hatti, Qode, Carchemish, Arzawa and Alashiya on, being cut off [i.e. destroyed] at one time. A camp was set up in Amurru. They desolated its people, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared before them. Their confederation was the Peleset, Tjeker, Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh, lands united. They laid their hands upon the land as far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting: “Our plans will succeed”.

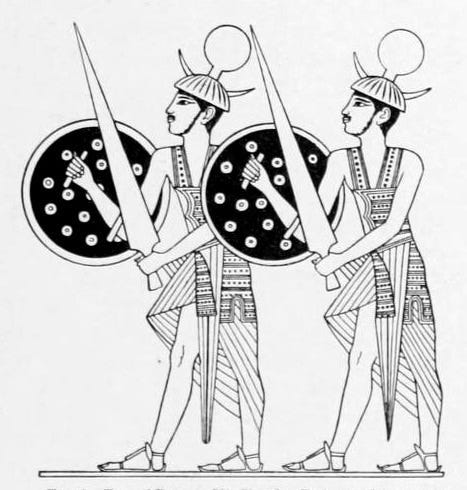

Interestingly, the Pharaoh doesn’t mention the Shereden. If we look closer at the two ships shown on the inscription, we’ll find that soldiers wearing horned helmets are associated with the Sherden. We can assume they were part of the invading force.

The inscription at Medinet Habu is important because it provides a description of the physical appearance of the Sea Peoples. We can get an idea about their attire and find clues about their possible origins.

The next source about the Sea Peoples is the Papyrus Harris I, the longest papyrus document ever found in Egypt. This text is from the early years of Ramesses IV's reign ( 1151 to 1145 BC) and describes a large-scale campaign against the Sea Peoples. Scholars connect this campaign with Ramesses III’s punitive actions against them. Ramesses III’s settling of captured Sherden and Weshesh in Egypt is the most important takeaway from this papyrus.

The Onomasticon of Amenope is our final source about the Sea Peoples. Dated 1100 BC, it provides evidence of Ramesses III settling many Sea Peoples in the Levant region, the land of ancient Canaan.

Let’s look at each group and discuss who they could be.

Identifying the Sea Peoples

The origins of the Sea Peoples remain a mystery. Their lack of written records makes it challenging to determine their identity. Scholars have theorized their possible identities using Egyptian, Hittite, and Canaanite sources, along with archaeological evidence.

Sherden

The Sherden were among the earliest Sea Peoples mentioned in the Amarna letters. They served in the legions of Pharaoh Ramesses II, including his personal guard. But by the time of Merneptah, they were part of a coalition of Sea Peoples fighting the Egyptians.

Some scholars believe they are related to ancient Sardinians because figurines of ancient peoples wearing armor and horned helmets matching Egyptian descriptions were found in Sardinia and Corsica.

The linguistic similarity between Sherden and Sardinia is also an argument in favor of this theory.

Another theory suggests they originated from Western Anatolia, from the Lydian capital Sardis. Scholars favoring this theory suggest that Shereden moved from Anatolia to Sardinia during the late Bronze Age collapse.

Though archaeological evidence points to the Shereden being based out of Sardinia, there is no conclusive evidence if they were native to the region or moved there from Anatolia.

Lukka

Lukka was the first of the Sea Peoples mentioned in ancient sources. Scholars believe they may have been the Lycians of Western Anatolia. Lukka were likely vassals of the Hittites, but there is no proof of any treaties with the Hittites or the mention of any Lukka ruler. Hittite sources dating to the mid-15th century tell us the Lukka attacked the Hittites and denounced their gods.

The Amarna letters include an appeal from the king of Alashiya to the Pharaoh Akhenaten for help fighting the Lukka. They teamed up with the Hittites in 1274 to fight the Egyptians at Kadesh.

Remember Ammurapi’s desperate plea for help? He says his ships were in the land of Lukka, which tells us they were a coastal people.

We can assume the Lukka were Anatolian people with a fickle alliance with the Hittites.

Weshesh

They were mentioned as part of the alliance that attacked Egypt during Ramesses III’s reign. We don’t know much about them. Some scholars associate them with the legendary city of Troy. The term Weshesh might be derived from the Hittite name for Troy, Wilusa. However, the links are tenuous, and limited evidence supports this theory.

Ekwesh

Most scholars suggest the Ekwesh were likely Achaeans, an ancient Greek tribe referred to in the Hittite sources as Ahiyyawa. Merneptah’s inscriptions suggest they were the largest group of the Sea Peoples. The Achaeans were present in Crete, Cyprus, and the Anatolian coast. There’s a possibility the Ekwesh and the Pelest allied when they colonized Crete. These new waves of immigrants brought the Mycenaean IIIC style pottery seen all over the island and later in the Levant.

Peleset

Some historians think the Peleset were the ancestors of the biblical Philistines who settled in the Levant. They may have come from Crete, but it’s unclear if they were indigenous to the region or immigrated there.

Archaeologists point to the introduction of Mycenaean IIIC-style pottery in the Levant as evidence for the Cretan origins of the Philistines. Other scholars suggest Ramesses III, after vanquishing the Peleset, settled them in Canaan.

Sheklesh

They are one of the more obscure Sea Peoples. Two contrasting theories of their origins exist. One suggests they came from Sagalassos in Pisidia, southwestern Anatolia. The other says they could’ve originated in Sicily. There is no academic consensus about their origins.

Teresh

This is one of the most intriguing groups, as they may have descended from the legendary city of Troy. Troy was a Hittite client state. One Hittite record refers to Troy as “Tarushia.” This could explain Teresh's linguistic similarity.

Is it possible that the survivors of Troy’s ruined city took up arms and began conquering other cities?

Another possibility is that Teresh were Tyresians, a group of pirates mentioned in the Hymn of Dinosyus, attributed to Homer. They had well-decked ships capable of an amphibious assault, like the one on Egypt.

Other scholars believe the Teresh could be the Etruscans of the Tyrrhenian Sea, the water body between western Italy, Corsica, and Sardinia. Etruscans lived in Italy before the rise of the Romans.

Tjekker

This group’s identity is unknown. They are shown wearing hoplite-like plumes on their helmets, leading some scholars to believe they may have originated from the Aegean region, most likely based in Greece. The evidence is too limited to draw a definite conclusion.

Denyen

According to Egyptian records, the Denyen were one of the major Sea Peoples. They are mentioned in Egyptian, Hittite, and later classical sources under different names, such as Danuna, Danaoi, Dene, and Danian.

There are different theories on their origins. Many scholars suggest Denyen was the Achaean Greek tribe Danoi. Homer refers to Greeks as Danaans, which led historians to link the Denyen to the Achaeans.

A less popular theory is that the Denyen was the biblical “tribe of Dan,” one of the twelve tribes of Israel. There isn’t much evidence connecting the two, except that both operated in the same geographical area.

Why were the Sea Peoples attacking civilizations?

A closer investigation suggests that the Sea Peoples were not unknown to the Near Eastern societies. They didn’t appear out of the blue. Recall the inscriptions of Merneptah. He says the Sea Peoples who fought for the Libyans arrived with women and children.

Why would someone go to war with their families?

As Egyptian and Hittite records show, if the civilizations were aware of them, we must ask what drove them to such actions. How did they muster the courage to attack the fortified Bronze Age cities?

The evidence seems to question the narrative that the Sea Peoples were marauding bands of invaders. According to current research, they may have been vassals of the kingdoms, mercenaries, or refugees fleeing climatic change and food scarcity.

Famines and volcanic eruptions were prevalent in the Late Bronze Age, and events like these may have had a cascading effect.

Famines cause food shortages, which also harm exports. Lower trade volume implies less revenue, which means less money for soldiers and mercenaries. If they weren’t paid, perhaps it was only a matter of time before they revolted.

Tribes used for fighting may have betrayed their old masters. If you recall, both Egyptians and the Hittites were using “Sea Peoples” as mercenaries in the infamous clash at Kadesh.

Food scarcity also drives people to migrate to new areas. Climate refugees are welcomed in some places but not in others. Perhaps not everyone took “no” for an answer. Perhaps the brave among them picked up arms for survival.

According to Egyptian texts, several Sea Peoples originated from Greece, where the Mycenaean civilization was destroyed. When a sophisticated and urbane economy crashes, numerous city-dwellers flee and become refugees.

It’s likely that as civilizations collapsed, their citizens joined the various Sea Peoples, increasing their numbers to the point where they could conquer neighboring states. In this context, we may view the Sea Peoples as a desperate, opportunistic group that exploited and emerged from the crumbling civilizations of the Eastern Mediterranean.

One of history’s most intriguing mysteries is that of the Sea Peoples. We can’t know for sure who they were, but there are hints about who they might have been. Recent research has gone some way to helping us explain where they might have come from and why they attacked the mighty Bronze Age civilizations.

Unlike in the past, we no longer see them as a group of pirates who showed up on city beaches, killed everyone, and then disappeared. Instead, they built new civilizations to replace the ones they had destroyed. However, it would be a long time before the new cultures reached the level of sophistication and urbanization seen during the Bronze Age.

References

Bryce, Trevor (2005). The Kingdom of the Hittites.

Dickinson, Oliver (2007). The Aegean from Bronze Age to Iron Age: Continuity and Change Between the Twelfth and Eighth Centuries BCE. Routledge.

Cline, Eric H. (2014). 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

D’Amato R., Salimbeti A. (2015). The Sea Peoples of the Mediterranean Bronze Age 1450–1100 BC. London: Osprey.

Extremely interesting-thank you. It's dizzying to think of how vast the past is, and how much is unknown, and how all is intricately interconnected

It can be argued, I suppose, that the more time passes by-the more "pirates" can be seen as building other civilisations, not simply tearing the other ones.

In my view, it is the Teresh who came from the Po valley region and migrated eastwards, leaving behind their cousins (the Etruscans and Rhaetians) who continued to speak the non Indo-european Tyrsenian languages that are indigenous to the “Italian” peninsula. The archeological Terramare culture, who abandoned the Po valley region en masse between 1200-1150 BCE, are in my view the most likely candidate for the Teresh recorded in the Egyptian sources.