Welcome to Cosmographia. This post is part of our series on Symbology. For the full map of posts, see here.

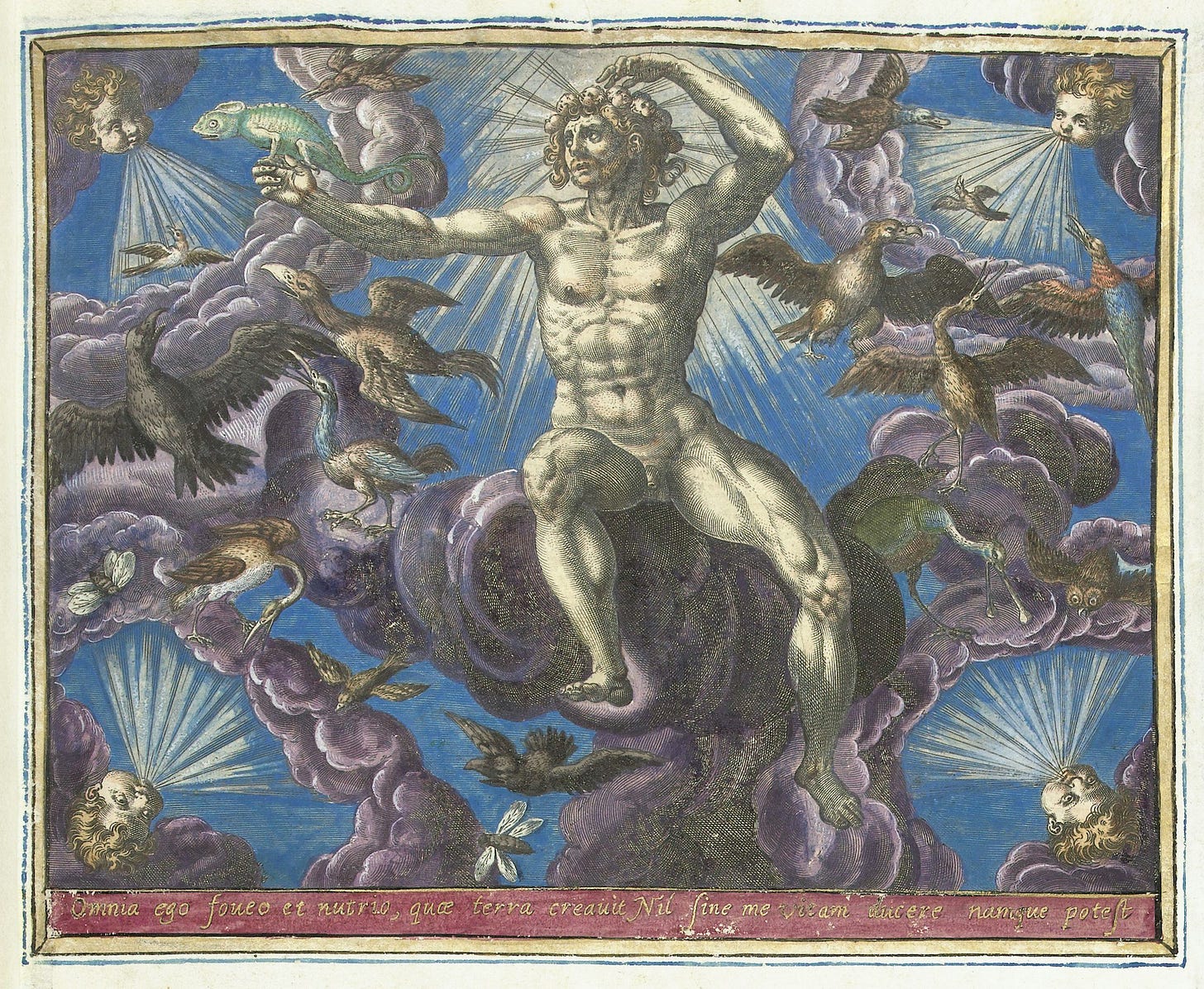

Air was an enigma to our ancestors. Somehow this invisible substance breathed life into living things, blew across the lands and seas in the form of wind, brought rain and waves crashing onto the Earth. Sometimes they could taste it, smell it, or feel it on their skin, but they could never see it, and that gave air a degree of mystery. In the long span of human history, it’s only very recently that we’ve come to understand what in fact this mysterious life-force actually is: a dispersed mixture of gases, the vast majority of which are completely useless to us.

Despite their ignorance, the ancients intuited that this mysterious substance was what animated living beings. In the Hebrew Bible, God breathes life into Adam, the first man, and in Navajo tradition the Wind breathes life into the first people, formed of corn. The very word ‘inspiration’ comes from Latin inspirare, meaning “to breathe into.” In languages across the world, the term for spirit (Latin spiritus, Greek pneuma, Hebrew ruach) also means breath or wind. Air came to be associated with the soul, an invisible symbol for the divine essence of life itself.

Wind deities and sky gods appear in almost every pantheon. The Mesopotamians worshipped Enlil, “Lord Wind”, god of the air and storms; his consort Ninlil embodied the southerly breeze while a demon, Pazuzu, blew evil winds from the northeast. The Egyptians personified the air as Shu, the deity who held up the sky, while the king of the pantheon, Amun, also likely originated as a wind deity. Classical Greece had the Anemoi, four winged gods for the cardinal winds (Boreas, Zephyrus, Notus, Eurus), and the wind-keeper Aeolus who bottled the winds in The Odyssey. In Rome, these became the Venti, while Jupiter himself, the sky father, wielded thunderous airs. In Norse cosmology, the god Njörðr could call forth favourable winds for Viking sailors. The world tree, Yggdrasil, was believed to sway gently under the force of cosmic winds, while a bitter freezing tempest was said to blow at Ragnarök, signalling the end of the world.

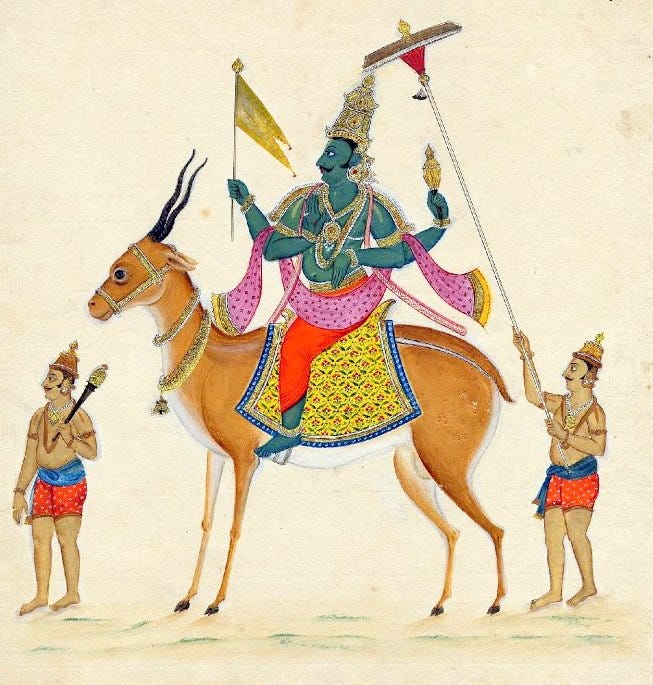

Far to the east, Fūjin, one of the oldest Shinto deities, governed the wind, and typically depicted carrying a bag of air. Similarly, in Taoist mythology the Count of Wind (Fengbo), was said to carry winds in a sack or bladder, releasing gales at will. Hindus have Vāyu, the breath of the world, representing prāṇa (life force) and movement. The Yoruba of West Africa venerate Ọya, ferocious orisha of wind and change; the Zulu speak of Inkanyamba, a serpent-like spirit residing in a whirlwind; and among Polynesians, the trickster Māui once goaded the winds into showing him their full strength, unleashing a storm of gargantuan proportions across Moana, the ocean.