Welcome to Cosmographia — a newsletter exploring the world and our place in it. For the full map of posts, see here.

There are a number of topics I have written about in the last six months or so which could do with an update. None of them quite merit a post of their own, so I thought I’d lump them all together. If you like this format, I might make this an irregular feature going forward, whenever there’s enough news to warrant one.

In this post:

Signs of extraterrestrial life support Nick Lane’s predictions

Am I descended from murderers?

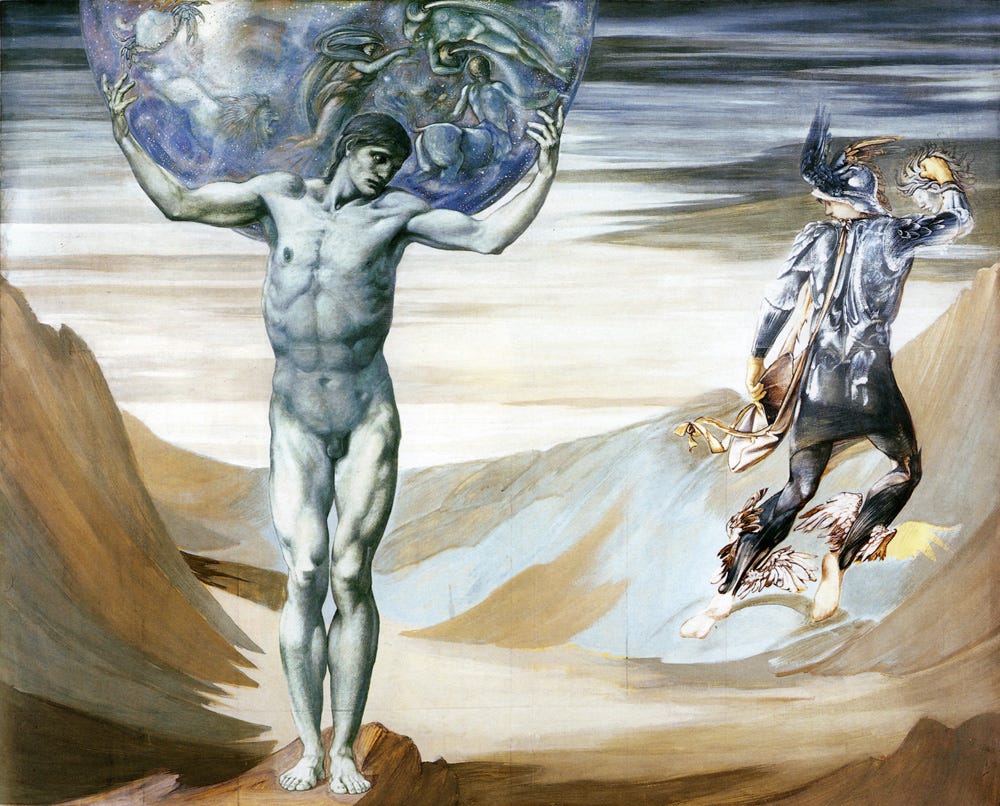

Sociocosmic models of the universe

Different climates produce different types of religion

Origins of Germanic peoples

Virality on Substack Notes follows the same pattern as other social media

Are Homo sapiens a hybrid species?

Signs of life on K2-18b

This is far from breaking news now, but a few weeks ago a paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters announced the discovery of dimethyl sulphide in the atmosphere of a distant exoplanet named K2-18b. This is exciting because as far as we know this chemical is only produced in large quantities by living organisms. Erik Hoel wrote up a great summary in this post:

If you accept the latest evidence at face value, alien life is now arguably the leading hypothesis. And K2-18b joins an ever-growing list of suggestive biosignatures on multiple exoplanets. There’s TOI-270d, sporting not only methane but also carbon disulfide (which on Earth mostly comes from biological processes), along with signs of an out-of-equilibrium atmosphere implying weird conditions we don’t understand… or life. There’s TRAPPIST-1e, another world which will soon be subject to James Webb Space Telescope observations with clear prior predictions about biosignatures from modeling. Even Proxima Centauri b—literally the closest exoplanet to Earth—could possibly have an oxygen atmosphere (which isn’t unique to life, but is suggestive), and at some point in the near future studies will examine its surface reflectance, since any vegetation will leave behind a detectable signature there.

If we hold that these biomarkers are in fact signs of life, they seem to give credence to Nick Lane’s ideas about the origins of life, which we explored last autumn.

The biochemist deviates from the mainstream scientific consensus on the cause of the Fermi paradox (or why we don’t see any evidence of alien civilisations among the stars). Most people think the Great Filter is abiogenesis — life beginning at all. Nick Lane disagrees:

Lane argues that while genes seem capable of endless diversity, energy does not. As such, he expects the basic metabolic processes that power life on earth (chemiosmosis) to be universal to all life, no matter where it is in the universe. This means that wherever we find the three ingredients that gave rise to life here — water, rock, and carbon dioxide — we should find life. Amazingly, these ingredients are incredibly common, and as such the universe might be teeming with life. But — and it’s a big but — there appears to be a stringent bottleneck at the jump from simple bacteria-like organisms to more complex lifeforms. It’s a depressing thought: we might well be surrounded by extra-terrestrial life on all sides, but none of it has evolved past simple bacteria.

If there is life on K2-18b, or T01-270d, or Proxima Centauri b, it seems likely it’s bacteria-like organisms producing these biomarkers. The fact we’ve found so many cases seems to support Nick Lane’s thesis that simple life is common. But there are still no signs of anything complex.

Am I descended from murderers?

Towards the end of last year, I wrote a four-part series on the prehistory of Europe, mapping the movements of people and cultures from the Neanderthals right up to the beginning of complex civilisation on the continent. In the third post in that series, I wrote of the nomadic pastoralist Yamnaya people:

Five thousand years ago, on the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea, a small group of farmers abandoned their homes and their fields. What they did next resulted in a demographic deluge that flooded Eurasia from the shores of the Atlantic to the mountains of Central India. Today, 3.2 billion humans — some 46% of all people on Earth — speak a descendant of their language. They were the Proto-Indo-Europeans, and they would transform world history forever.

Despite their migrations taking place deep among the misty swirls of prehistory, ancient DNA has allowed us to track the Yamnaya expansion across Europe and Asia. Genomics has revealed something rather macabre about these population movements:

The Y-chromosome haplogroup distinctive to the Yamnaya is R1b; for the CWC it’s R1a. As the Yamnaya moved southwestwards into the Balkans, and the CWC moved northwards into the Baltic and westwards into Poland and Germany, all other male haplogroups suddenly disappear in the genealogical record. There is only one explanation that fits the data: the nomads killed the men and took the women for wives.

After writing that post, I felt I had to know if I, like most people with European ancestry, was descended from the Yamnaya. So around Christmas time, I spat into a little plastic tube and sent off my DNA to a lab.