Welcome to Cosmographia. This post is part of our Cartography of Networks series. For the full map of posts, see here.

Sometime in the early 1140s, the scholar Gerard of Cremona grew bored of the philosophies of his teachers and left Northern Italy for the Iberian peninsula. He headed southwest, crossing the Rhône river before heading south through the Pyrenees, continuing on until he had reached the city of Toledo.

The southern half of what we now call Spain had been under Islamic rule for centuries, and the ruling dynasties of Al-Andalus had brought with them their rich heritage of classical scholarship. Though the texts of Plato, Aristotle, Euclid and other ancient scholars lived on in Byzantine Constantinople, they had long been forgotten in Western and Northern Europe. Thus, this was the only place on this side of the continent to read the works of the ancients, and their subsequent commentary and expansion by Arab thinkers. The libraries of Toledo were particularly full, brimming with thousands of tomes on geometry, philosophy, medicine, rhetoric, and more; as the city had just been conquered by Castile, it was safe for western scholars to visit for the first time in centuries.

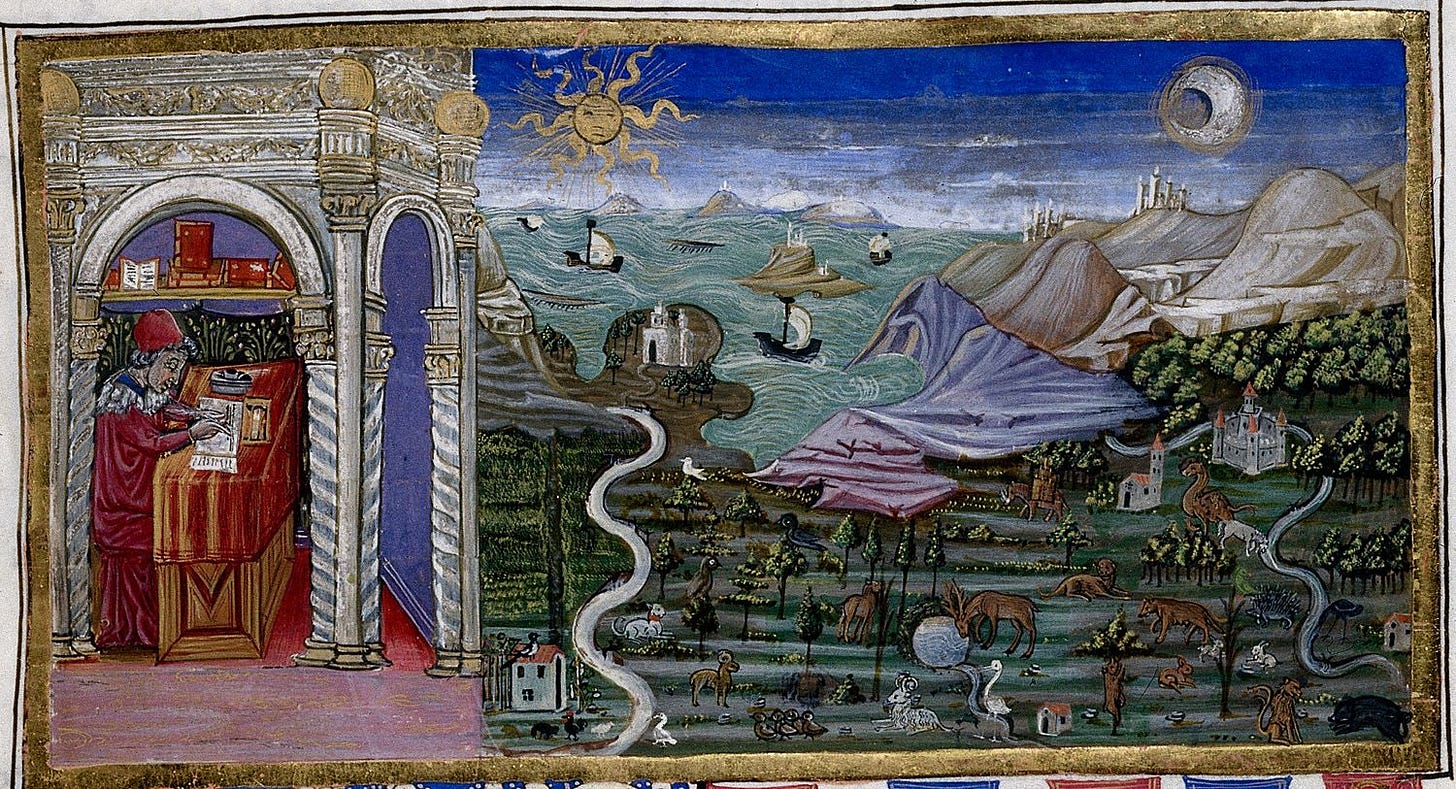

Gerard was hoping to find one particular text, the Almagest by Claudius Ptolemy, but he found so much more than that. Of course, the Muslim texts were written in the vernacular of Islam, Arabic, so Gerard set about learning the script so he could read the works himself. By the time the Italian died in 1187, Gerard had translated 87 books from Arabic to Latin, including originally Greek works like the Almagest, Aristotle’s On the Heavens, Archimedes’ On the Measurement of the Circle, and Euclid’s Elements of Geometry; as well as originally Arabic works like Jabir ibn Aflah's Elementa astronomica, al-Khwarizmi’s On Algebra and Almucabala, and works by al-Razi.

The Renaissance had begun… or had it?

In the 1330s, the Tuscan poet, scholar, and early humanist, Petrarch, birthed the idea of the ‘Dark Ages’ when he wrote:

Amidst the errors there shone forth men of genius; no less keen were their eyes, although they were surrounded by darkness and dense gloom.

From his vantage point on the Italian peninsula in the Middle Ages, recent times had seemed intellectually ‘dark’ compared to the ‘light’ of classical antiquity. While this may have been true of Italy, and Europe more widely, this was not the case elsewhere.

Instead, the intellectual tradition had not just continued but thrived in key locations all across the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, where centres of learning — or in network speak, ‘hubs’ — had prioritised and encouraged scholarship, making progress across a diverse range of fields. Despite this fact, the Middle Millennium — the traditional period between the end of antiquity and the start of the Renaissance (c. 500 - 1500 AD) — is often ignored in Eurocentric histories of knowledge.

Let’s correct this oversight by looking at eleven hubs of Dark Age scholarship, and then consider the edges that allowed information and ideas to flow between them.

Hubs

Alexandria

At the turn of the 6th century, Alexandria still held onto much of its former glory. Though the great library was long gone, the city remained a vibrant centre of intellectual activity; obviously Jewish, Christian, and Gnostic scholarship abounded, but so too did influences from Buddhism and Zoroastrianism, while devotees of Hermes Trismegistus could also still be found here.

Working at this time was John Philoponus, whose commentary on the works of Aristotle from a Christian perspective would prove influential far beyond his lifetime. When Alexandria fell to Arab conquest in the 640s, his works were among those that found their way into the hands of Islamic scholars. Ironically, the Christian philosopher’s ideas would go on to shape Islamic thought for centuries after they had been condemned as heresy in Christendom.

Alexandria’s last great contribution to world knowledge was to serve as a bridge — not just between different faiths and philosophies, but between historical eras. As the classical world faded and new powers rose, Alexandria ensured that the flame of inquiry passed on.

The Court of Khosrow I Anushirvan

In 529 AD, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian the Great closed the Athenian Academy — the school began by Plato himself almost a thousand years before — for its incompatibility with Christian doctrine. Turned out from their home, the Greek philosophers who taught at the academy headed east to the court of Sasanian emperor Khosrow I Anushirvan. Notable figures among these scholars were: author of Solutiones ad Chosroem, Priscianus Lydus, and Simplicius and Damascius, both commentators on Aristotle.

Works arrived from the east too: the collection of Indian fables known as the Panchatantra were translated into Arabic in the Sasanian capital. Meanwhile several works on astrology were attributed to another court official, Buzurjmihr, who was also the subject of a legend in which he was the first person in Persia to understand the rules of chess.

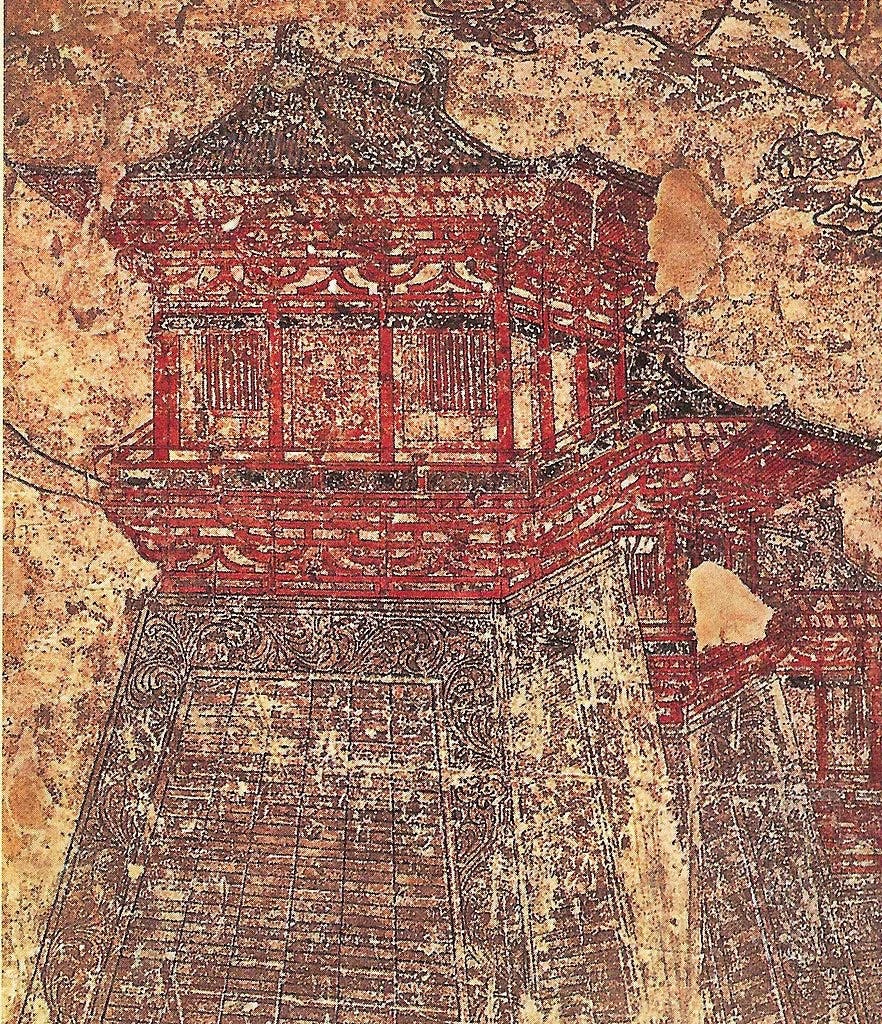

Tang Dynasty China

The Tang dynasty, established in 618 AD, rose to prominence at the same time as Islam to its west. Its capital, Chang’an (now Xi’an), was the world’s most populous city and marked the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, which had begun to flourish once more. This strategic position allowed Chang’an to emerge as a melting pot of diverse cultures and ideas. The imperial court attracted foreign intellectuals, including Persian astronomers and musicians, and Indian astronomers Qutan Luo and Gautama Siddhartha, who held prestigious positions as directors of the astronomical bureau.