Welcome to Cosmographia. This post is part of our Cartography of Networks series. For the full map of posts, see here.

“And this also,” said Marlow suddenly, “has been one of the dark places of the earth.”

— Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

In public discourse today, slavery is treated as something akin to the ‘original sin’ of Western civilisation — a taint inherited from history that still haunts our politics centuries after its prohibition. Indeed, the last few years saw something of an (unresolved) racial reckoning in the United States, with questions about whether the nation had sufficiently made up for its early crimes of slavery, segregation, and institutionalised racism increasingly dominating national politics. Here in the UK, it was headline news in 2015 that then Prime Minister David Cameron’s ancestors had once owned slaves — the implication being that he was tarnished by the actions of his progenitors long since passed, that his family’s wealth had been built on the back of forced labour. At the same time as activists in the US were calling for reparations for African Americans, so too were countries like Jamaica, Nigeria, and Senegal calling for reparations from their former colonisers for the role they had played in the infamous transatlantic slave trade, and the devastation it had wrought on the people of those territories.

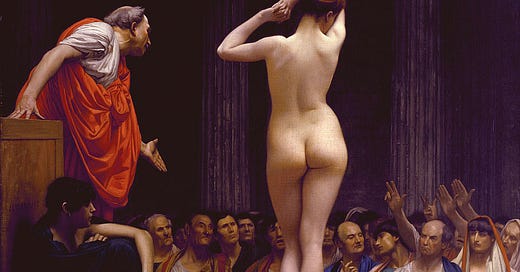

Most people alive today, I hope, would now agree that treating another human as property, as chattel to be bought and sold, is a uniquely wicked and degrading crime. But the interesting thing about that moral claim — which you and I take as among the most basic facts of human dignity — is just how incomprehensible it would have been to most human societies in history. As an institution, slavery was taken as a fact of life, as essential to the workings of both an economy and a household, whether in Ancient Rome, Early Modern Mesoamerica, or Mediaeval China. It is often said that prostitution is the world’s oldest profession, but slaving might well be able to give it a run for its money.

It’s all too easy to take the moral norms of our day for granted, without giving much thought as to how novel many of them are. Our world is undoubtedly better off for having so firmly consigned slavery to the ethical dustbin (even if we haven’t yet fully eradicated all forms of its practice), but perhaps we do ourselves a disservice by not coming to terms with how deep in our history as a species it goes.

The uncomfortable reality is that history is littered with slave networks; in fact they are probably among the oldest and longest lasting human networks in history. I say this not to downplay the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade in particular — as we shall see, the scale of that network was truly something unprecedented — but instead to underscore a simple point: no matter where you are, no matter where you go, you too tread one of the dark places of the earth.

There is a common misconception, popularised in ‘Big History’ books like those by Yuval Noah Harari, Jared Diamond, and Steven Pinker, that slavery — along with many of the other ills of human society — began with the invention of agriculture. This is not true.

We now have evidence that pre-agricultural societies kept slaves. For example, the indigenous Northwest Coast societies of America practiced chattel slavery as far back as 1850 BC, when they were still foragers. It wasn’t a small minority either; it’s estimated hereditary slaves made up a quarter of the local population, which is roughly akin to the free/slave ratio of classical Athens or the colonial-period American South.

Though slavery wasn’t ubiquitous among hunter-gatherer societies — indeed, the Yurok people in California had a much more egalitarian social structure despite being only a few hundred miles to the south — it does mean the old narrative that inequality was invented with the plough is no longer fit for purpose. Interestingly, researchers have identified that the prevalence of slavery among these groups isn’t correlated with either war or population pressures. Instead, the most likely predictor appears to be the presence of “defensible clumped resources” — in other words, when valuable resources are concentrated in one place and can be controlled by a few people. One could characterise a lot of modern geopolitics in the same way.

As humanity began to urbanise after the Neolithic Revolution, we see immediate evidence of slavery in most of the emergent cities. Some of the earliest written records in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica, whether law codes or business contracts, refer to enslaved people, indicating the practice was already widespread by the time those societies invented writing. But it wasn’t just urban centres: the hyper-patriarchal elites of Bronze Age pastoralist cultures like the Yamnaya and Corded Ware cultures kept vast harems of sex slaves too.

In all of these early societies, slaves were typically acquired through warfare, raids, or as punishment for crimes and debts. The slaving networks were therefore mostly local. However, as civilisations grew more complex, so did their systems of human bondage.