Welcome to Cosmographia. This post is part of our series on Symbology. For the full map of posts, see here.

Whatever the Earth feeds and grows is restored to Earth. And since she surely is the womb of all things and their common grave, Earth must dwindle, you see, and take on growth again.

— Lucretius, On the Nature of Things (c. 1st century BC)

As well as being the one of the five classical elements, Earth has been one of humanity’s most enduring symbols. Invariably personified as a woman, Mother Earth, Mother Nature, or the Earth Mother, appears in many forms — as a life-giving goddess, as the soil and land that sustains us, as the spherical planet we call home.

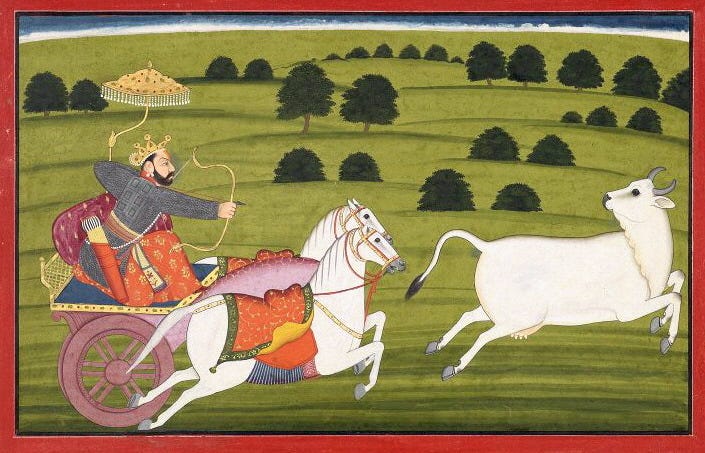

Countless cultures portray the Earth as a Great Mother, who existed at the dawn of creation and gave birth to all things. The Greeks had Gaea, or Gaia, the first mother who formed from the primordial abyss of Khaos to give birth to the Sky (Uranus) — from whose sexual union she bore the Titans, Cyclopes, and Giants — and the Sea (Pontus) — with whom she birthed the first sea gods. The Roman equivalent was Tellus, or Terra, or as the Etruscans called her, Cel; the Sumerians had the primordial earth goddess, Ki, consort of the sky-god An; the Norse had Jörð, mother of Thor and mistress of Odin; the Irish Celts had Danu, mother to all other gods, associated with earthly bounty and fertility; the Incas had Pachamama, the Andean Corn-Mother who they honoured with offerings of coca leaves and libations; the Balts had Zemes Māte, the female aspect of nature and source of all life; the Hindus spoke of Prithvi, consort of the sky-god Dyaus in the Vedas, sometimes depicted as a cow; the Akan people of West Africa had Asase Yaa, the soil itself, provider of fertility and sustenance; while the Māori told of Papatūānuku — the Earth Mother who, with the Sky Father Ranginui, bore all beings.1

It’s interesting how common the union between the female Earth and male Sky is across cultures, even among those that don’t share an Indo-European heritage. Clearly, agricultural bounty is easy to metaphorise as feminine, with the soil acting as the womb for all life. Meanwhile, the Sky, temperamental and looming above, often emerges as a tyrannous father-figure.

However, these roles aren’t universal: in Egyptian mythology the genders are reversed, with the Earth (Geb) male, and the Sky (Nut) female. Here, as well as making the crops grow, Geb was feared as the father of snakes and the cause of earthquakes. Interestingly, the womb metaphor is invoked here too; in this case the goddess Nut swallows the Sun and Moon every day at dusk, before giving birth to them anew at dawn. Eating appears in Aztec mythology too: Cōātlīcue the mother-goddess who wears a skirt of writhing snakes, both creator and destroyer, was depicted with limp breasts (symbolising that she had nourished many) and a necklace of hands, hearts, and skulls (symbolising that she feeds on corpses, just as the earth consumes all that dies). In this case, the mother of the gods birthed not the sky but the sun, Huītzilōpōchtli, who was so key to Aztec belief.

The Syilx of the Pacific Northwest region of North America used to speak of the Earth as the ‘Old One’. Her flesh was the soil, her hair the plants, her bones rocks, and her breath the wind. The Hopi and Navajo, meanwhile, spoke of Kokyangwuti (Spider Grandmother) who crafted animals and man out of clay and taught them how to grow crops. The Gaulish Celts worshiped Abnoba, the nature goddess who personified the woods, mountains, and the hunt; something similar is found in the Hindu deity Aranyani, who was associated with forests and animals, almost exactly the same as the Yoruba goddess, Orisha. As I write this, it’s the time of year in Japan when Konohanasakuya-hime, the personification of Mount Fuji and the cherry blossom (sakura), reveals herself. Meanwhile, the rest of nature is embodied in Shinto belief not as one single Earth Mother, but countless kami (spirits) that inhabit features of the land like mountains, rocks, fields, and trees.

In Norse mythology, the Earth was formed from the vast carcass of the giant Ymir, slain by the gods Odin, Vili, and Vé, who’s grandfather had been licked out of the ice by the primordial cow, Auðumbla. In Zoroastrian belief, Zam (Earth) is both an element and a minor divinity. According to the Bundahishn, a cosmogonical text, Zam was the third of the primordial creations, after the sky and waters, coming just before plants and fire.