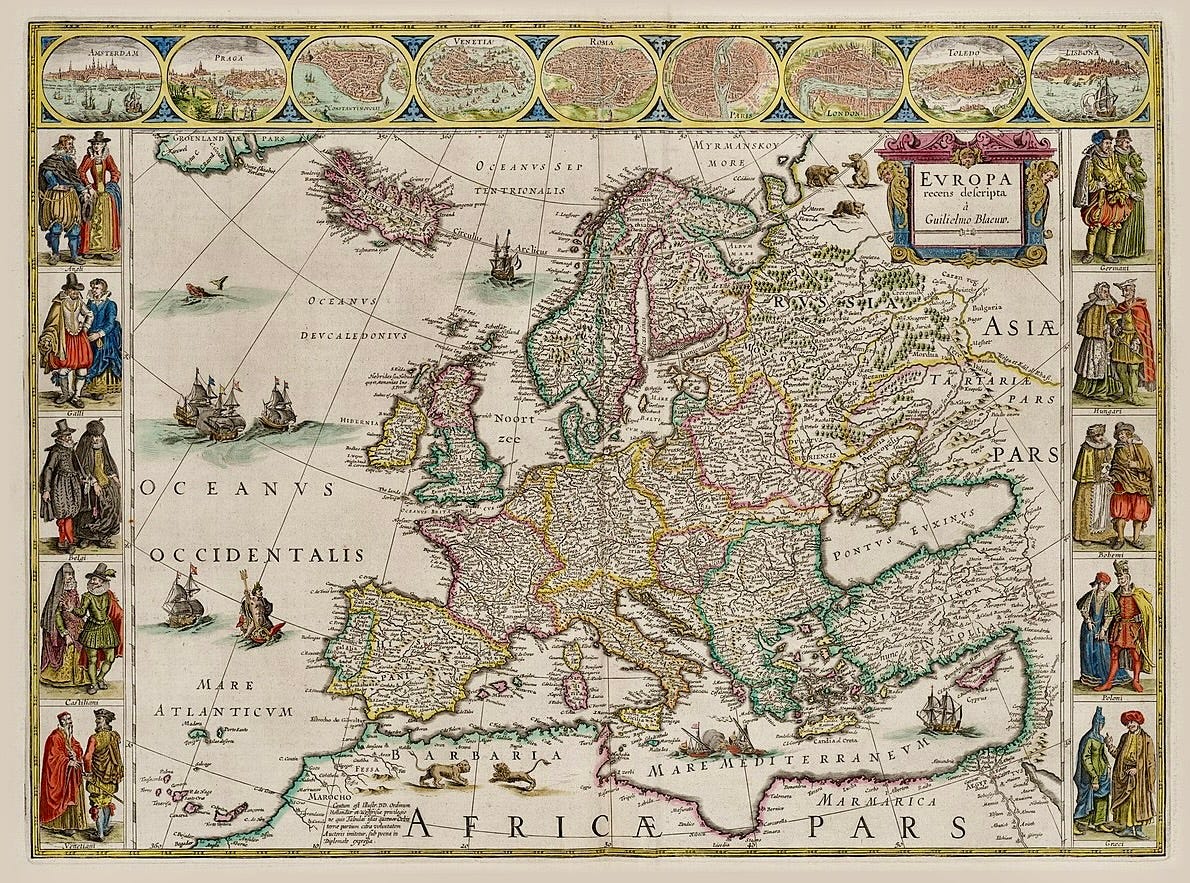

Welcome to Cosmographia — a newsletter dedicated to exploring the world and our place in it. For the full map of Cosmographia posts, see here.

Most histories of Europe start with Greece. Though the area saw the continent’s first literate societies, human settlement here has far deeper roots than the Minoan or Mycenaean civilisations.

For centuries we could only grope in the dark at times such long past, predating any written sources, but the ongoing revolution in the science of history has begun to lift back the veil on humanity’s deep past. Where once we had to piece together an incomplete picture from scattered fragments of pottery or the ruins of burial mounds, now we have the ability to trace genealogies through millennia, reveal old enemies are even older than we thought, and track the influence of climatic change on the populations of ancient humans.

Europe’s prehistory began long before Homo sapiens first walked the African sands and ended when writing first emerged on the islands of the Aegean. From those first scripts carved into the rock came a mythology of origin: Homer, Hesiod, and the other poets sang of a primordial time when gods and heroes once walked the Earth. We’ve never lost the urge to look back and wonder where we came from. Though the story is far from complete, modern science has given us the beginnings of an answer.

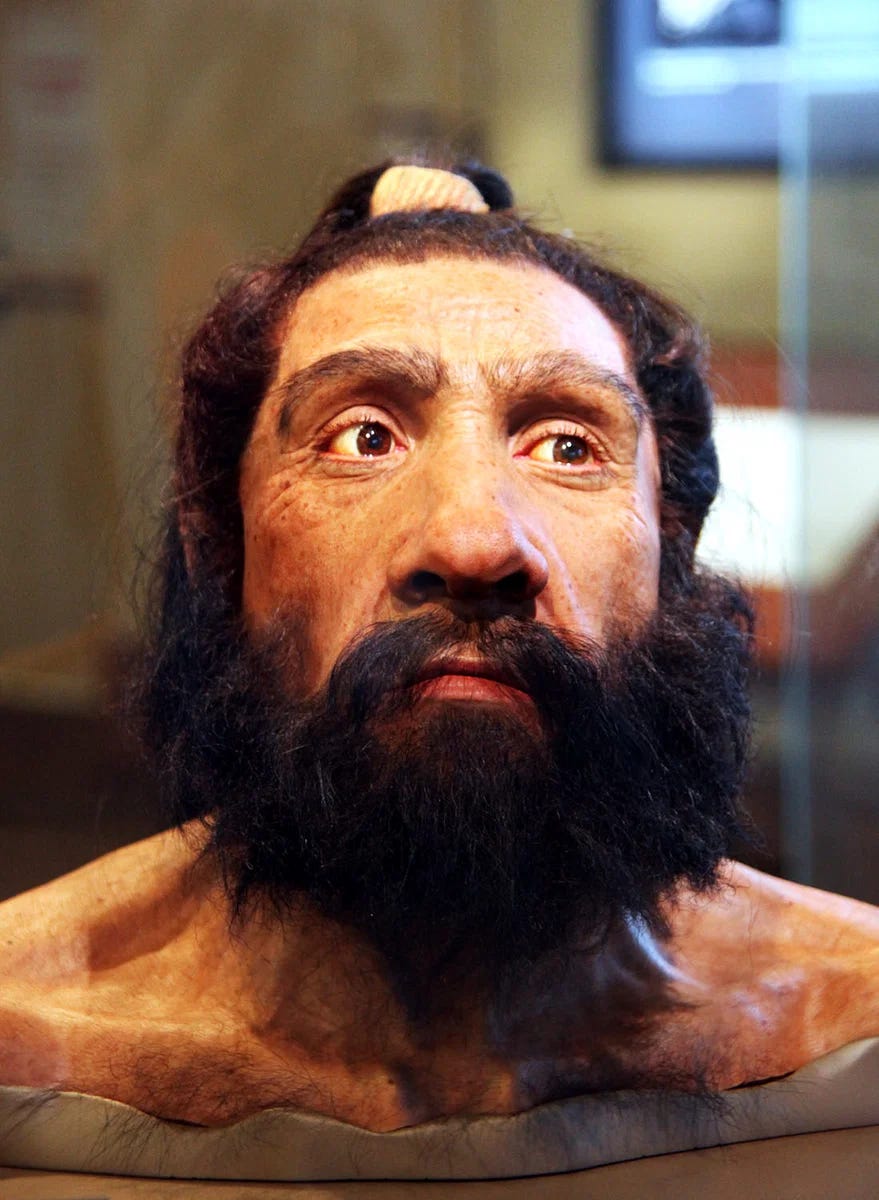

Pax Neanderthalensis (~430,000-40,000 BP)

Long before anything resembling a modern European ever wandered this continent, it was home to the Neanderthals.1 For over 350,000 years our closest evolutionary cousins dominated Eurasia from the shores of the Atlantic through to southern Siberia, their populations rising and falling with the harsh glacial cycles of the Middle to Late Pleistocene. Estimates based on mitochondrial DNA suggest that at their peak, Neanderthals numbered only 52,000 concurrent individuals — roughly the same population as the small English town of Reigate.

Recent research has dispelled the Victorian notion that the Neanderthals were brutish cavemen. In fact, ever more evidence points to their sophistication. Neanderthals used a variety of tools, controlled fire, crafted adhesives, wore simple wrap-clothing, created jewellery from eagle talons and seashells, and may have even engaged in symbolic cultural practices. Their care for the disabled among them shows evidence of deep compassion, while their burial of their dead suggests they were cognisant of the finitude of life. In truth, the more we learn about the Neanderthals, the more they seem like us.

The Neanderthal’s robust bodies, squatter than ours, were perfectly adapted to Ice Age Europe; their shorter limbs made them more energy efficient in the cold weather, a necessary adaptation for living in Eurasia, which during the last ice age was significantly colder than Africa, where we would eventually emerge. DNA analysis has revealed the Neanderthals had a higher proportion of fast-twitch muscle fibres, suggesting they were powerful sprinters well-suited to ambush hunting in the dense forests they preferred to open grassland. It’s thought they might have had lightish-coloured skin and dark or red hair. Their brains were larger even than our own, suggesting they at least had the biological capacity for high intelligence. Indeed they share the FOXP2 gene with us, which is related to speech and language (whether that means they had the same complex language abilities as us is still unclear). It has also been postulated Neanderthals were more creative in their toolmaking than the earliest modern humans, whom they overlapped with in Europe for at least 15,000 years.

Why then did they disappear? This remains an area of fierce debate, but recent work by French archaeologist Ludovic Slimak has asked whether the Neanderthals were simply less social than us. Indeed they tended to operate in smaller groups, and analysis of the DNA of a particular band of late Neanderthals has revealed they remained isolated not only from modern humans nearby, but from other Neanderthal groups only a week’s walk away — for over 50,000 years! Given there don’t seem to have been any geographical barriers preventing them mixing with other groups, Slimak has suggested that they may just have been extremely xenophobic. By refusing to play with others, perhaps the Neanderthals left themselves open to being outcompeted by a more social species.

Whatever the reason, the last Neanderthal sputtered her final breath some 40,000 years ago, leaving the newest species of human to roam the forests of Europe alone. Though as we’ll see, they live on in us.