Welcome to Cosmographia — a newsletter dedicated to exploring the world and our place in it. For the full map of posts, see here.

Few of us spend much time thinking about toponymy — the study of place names. Instead, most of us use the names for lands and nations that we were taught as children, without ever giving much thought as to where they came from.

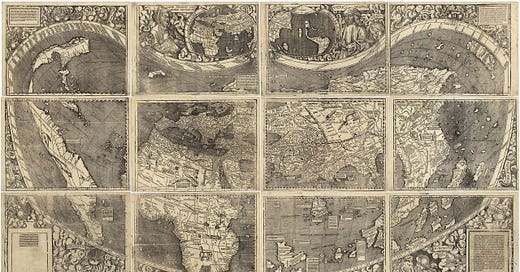

I doubt, for example, that most of my fellow country-people are aware that ‘Britain’ comes from the Celtic Common Brittonic word *Pritanī — meaning something like, “Land of the Painted Ones.” Similarly, I suspect most Americans — including a certain someone who has been very keen on names, recently — have little knowledge of Amerigo Vespucci, the Florentine navigator. Still fewer will be familiar with the part played by two obscure German scholars, who in a tiny French town in the 16th-century gave the Americas its name.

We all know the story: Christopher Columbus set sail from Palos, Spain on the evening of 3rd August, 1492, sailing west until he made landfall on an island in the Bahamas some two months later. Though he didn’t ‘discover’ the Americas — there were already quite a few people living there already, of course; not to mention the fact he wasn’t even the first European to reach the continent, that honour goes to Viking sailors almost five centuries before — his voyage remains a major hinge moment in history, ushering in as it did the Age of Discovery and the subsequent Columbian exchange between the Old World and New. Columbus is today routinely portrayed as a villain for his actions in the Caribbean — and with good reason — but something that’s often missed is that he was controversial even in his own time.

After his second and third voyages west, the King and Queen of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, repeatedly and exasperatedly scolded the Genoan for enslaving members of the indigenous Taíno people, whom they wanted treated with dignity as ‘potential Christians’ and, in their minds, their newest subjects. Similarly condemnatory was the Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas, who campaigned for fifty years against the brutality inflicted upon the indigenous peoples of the Americas — his efforts show our outrage at the crimes of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade are as least as old as the activities themselves. Indeed, one can read even in Columbus’ own writings a growing horror of what he himself is doing.

Eventually, after a growing sense that Columbus was losing his grip on the situation, the pioneer of the passage west was stripped of his monopoly rights, and others were permitted to voyage to the New World.

One of those who tossed their lot to fortune was the man mentioned above — Amerigo Vespucci. In 1499, the Florentine was aboard one of the four ships of a Spanish expedition dispatched to explore the large landmass first sighted by Columbus on his third voyage — a landmass we now know as the continent of South America, though the Genoan, who was almost certainly going mad by this point, naturally believed he had discovered the Garden of Eden.1 The four ships arrived somewhere off the coast of Suriname; two tracked the coast westwards towards Venezuela, while the other two — one of which was carrying Vespucci — headed south down the coast of Brazil. They passed two monumental rivers (the Amazon and Para) before eventually reaching an adverse current that they couldn’t pass. Forced to turn around, they headed back towards the island of Hispaniola, where they were able to get resupplied before heading back to Europe.

Upon his return, Vespucci was soon hired for another expedition — this time by King Manuel I of Portugal. He wanted to explore the landmass discovered by Pedro Álvares Cabal when he was trying to round the Cape of Good Hope by tacking west into the Atlantic. Not long before, the Portuguese had signed the Treaty of Tordesillas with the Spanish, the terms of which delineated any land to the west of a line of longitude cutting north to south through the Atlantic as belonging to Spain, and any land to the east as belonging to Portugal. Manuel was keen to determine where this strange land in the South Atlantic lay in relation to that line.

On 17th August 1501, the expedition of three ships landed at Brazil at a latitude of around 6° south. Supposedly they encountered a group of hostile natives who killed and ate one of the crewmen — why the survivors would have hung around long enough to witness the cannibalism after a fraught battle in a strange land is unclear (I’m sceptical of the whole business). From there they sailed on south, arriving at a large bay on 1st January 1502, hence naming it Rio de Janeiro. They continued on to approximately 25° south (almost to the southernmost edge of modern Brazil), before turning back.

On his return home later that year, Vespucci’s letters broke the news of the voyage’s discoveries, with Florentine publishers jumping at the chance to print his account. His descriptions of a giant landmass stretching thousands of miles south of the equator was nothing short of a sensation.

Up until this point, the extent to what these voyagers were finding out there in the west Atlantic hadn’t been fully understood back in Europe. Columbus’ initial discovery of the islands of the Caribbean was mostly interpreted as another set of Canary Islands — not nothing, but not world-shattering either. Perhaps they could make a good waypoint on a route further east, to where the real action was: Asia. This was partially down to Columbus himself: he was incapable of admitting to himself or anyone else that he had discovered anything other than islands just off the coast of China. At one stage he forced his men to sign a contract holding them to this fact on pain of getting their tongues cut out (he was a strange man!), and even dispatched an emissary with a letter for the Great Khan of China into the interior of Cuba. Until the day he died in 1506, he was adamant he had found the ‘Indies’.

This point was made most astutely by Italo Calvino in his short essay, “How New the New World Was”. He writes, “Discovering the New World was a very difficult enterprise, as we have all been taught. But even more difficult, once the New World was discovered, was seeing it, understanding that it was new, entirely new, different from anything one had expected to find as new.” It’s so easy to forget this now, but for years the Europeans weren’t able to see what they had discovered for what it was — something new.

Even Vespucci couldn’t see it, writing, “We concluded that this was continental land — which I esteem to be bounded by the eastern part of Asia.” If that had been true, the world would have in fact been made smaller by the previous decade’s discoveries, not larger — for this would have meant the contemporary calculations for the size of the Earth (which weren’t too far off reality) were massively overexaggerated. Vespucci’s publishers though, were more interested in making a quick buck. They doctored one of his letters, so it began:

In the past, I have written to you in rather ample detail about my return from those new regions…and which can be called a new world, since our ancestors had no knowledge of them, and they are entirely new matter to those who hear about them. Indeed, it surpasses the opinions of our ancient authorities, since most of them assert there is no continent south of the equator… [But] I have discovered a continent in those southern regions that is inhabited by more numerous peoples and animals than in our Europe, or Asia, or Africa.

They published it under the title Mundus Novus, or New World, and it quickly became a bestseller.