The Descent of Man

Holy Land: Edition VII

Welcome to

. This post is part of our Holy Land series. For the full map of Cosmographia posts, see here.

Then God blessed Noah and his sons, saying to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number and fill the earth.”

Genesis 9:1

In the old world, lineage was all.

Kings begat kings, peasants begat peasants, and gods begat gods.

For the Israelites, YHWH's chosen people, their lineage was both their identity and their destiny. It was the thread that connected them to the divine covenant, the promise of a land to call their own, and the hope of a future Messiah.

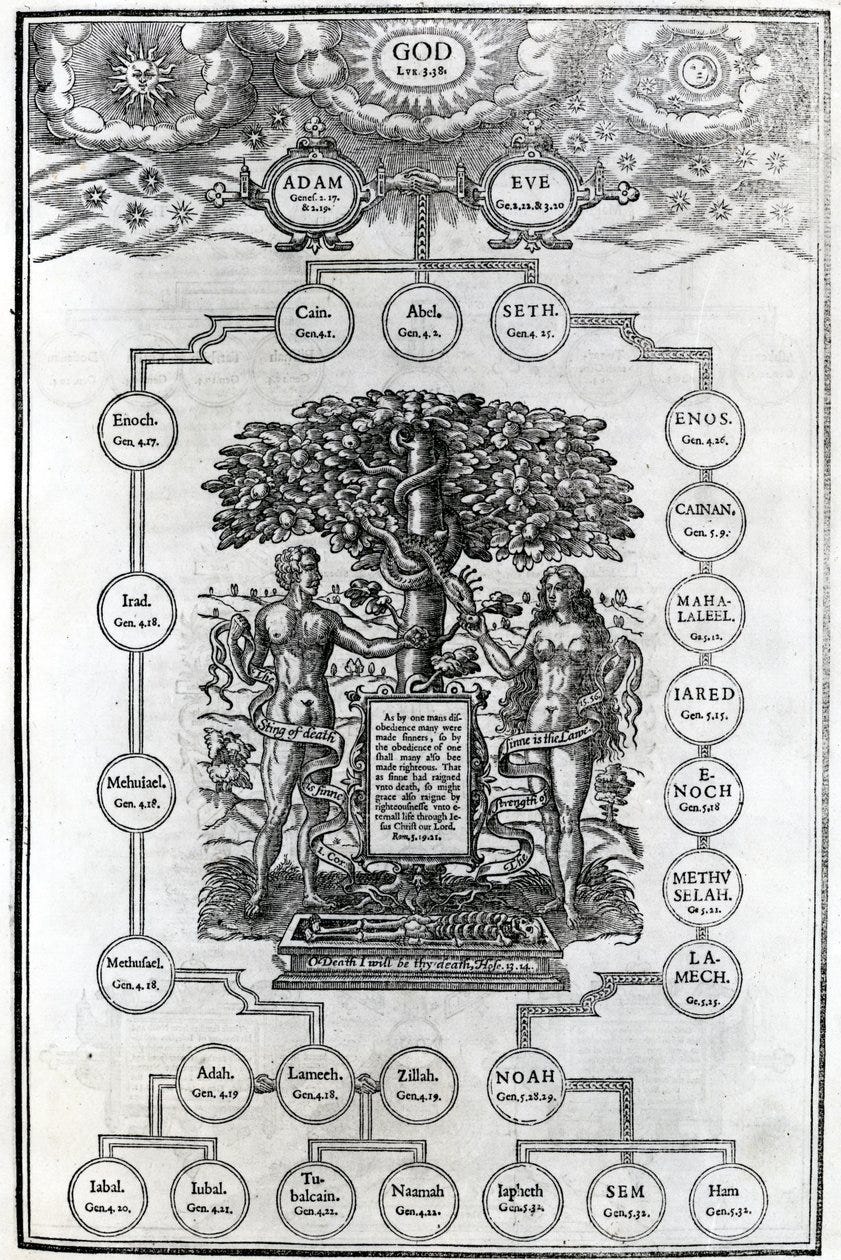

This is why, when the Israelites were cobbling together the narratives that would become the Hebrew Bible (c. 8th-5th centuries BC), so much ink was spent furiously documenting family trees, tracing the lines of fathers and sons, ancestors and descendants. These genealogies were more than lists; they were the keys to understanding one's place in God's plan. Each name, each begat, was a reminder of where they had come from, and a promise of where they were going. For the Israelites, lineage was not just history; it was prophecy.

At a time when greater powers — the Egyptians, Babylonians, and Assyrians — constantly threatened to erode their identity, the Israelites clung to their lineages as a way to preserve their sense of self. Even in their Babylonian exile, intermarriage with outsiders was seen as a threat to both religious and ethnic purity, a dilution of the sacred bloodlines.

For the Israelites believed that their forefathers, Noah, Abraham, and David, had entered into a sacred covenant with God, a promise that extended to them, their descendants. To be a part of this lineage was to inherit a portion of the Promised Land, a birthright that was jealously guarded and passed down through the generations.1

But lineage was not just about inheritance; it also determined one's role in society and in the service of God. The descendants of Levi were set apart as the priestly class, while the sons of Aaron were ordained as high priests. To be born into the right family was to be born into a life of purpose and duty.

Yet, lineage could work both ways: the sins of the father could taint the destiny of his descendants. The wicked men and women swept away in the Great Flood were those of Cain's line, forever marked by their ancestor's heinous crime. Only righteous Noah and his family, descendants of Seth, Adam and Eve’s third son, and thus untouched by Cain’s sin, were spared to begin anew.

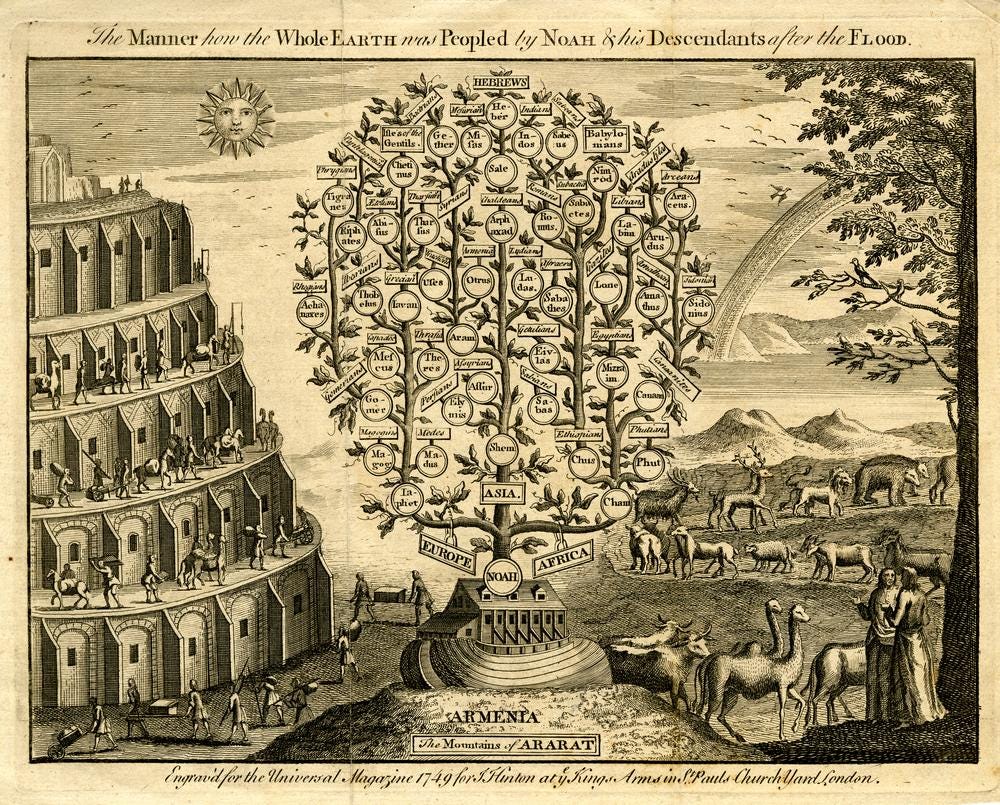

As Genesis tells it, after being borne upon the floodwaters for 150 days, Noah’s ark finally came to rest on Mount Ararat, Armenia. Emerging from the great ship were the only people left in the world: Noah, his three sons, Japheth, Shem, and Ham, and the four wives.2 It was from these three sons that the world was populated once again.

The ‘Table of Nations’ in Genesis 10, compiled over the course of several centuries,3 presents a detailed genealogy of the descendants of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, the peoples for which they’re named, and the regions they came to inhabit. The table makes claims to name all the peoples of the world, but in reality only describes the Eastern Mediterranean and the Ancient Near East, which were the lands known to the Israelites at the time. It seems the author(s) of Genesis 10 looked about their world, and named a descendant of Noah for each of the peoples they saw. Geography through genealogy; a family tree as a map of the world.

In the wake of the Flood, the Tree of Man had been pruned of wickedness, and was now ready to grow again. It grew through three branches.

The Japhethites

The Bible isn’t clear on this point, but Japheth has often been taken to be the eldest of Noah’s sons. Josephus Flavius, the ancient Jewish historian, believed Japheth’s name to be a transliteration of the Greek Iapetos, the mythical Titan ancestor of the Hellenic peoples.