Welcome to Cosmographia. The following is part of our Atlas’ Notes series, featuring art, poetry, literature, cartography, and photography, all centred on a particular place. For the full map of Cosmographia posts, see here.

The name “Punjab” comes from Persian, but its components (پنج, panj, “five” and آب, āb, “water”) are cognates of the Sanskrit words पञ्च, pañca, “five” and अप्, áp, “water”. “Punjab”, therefore, translates to “The Land of Five Waters,” referring to the rivers Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas.

These rivers, tributaries of the Indus River, nourished one of the Bronze Age’s greatest civilisations — the Indus Valley Civilisation (c. 3300—1300 BC). The historical region of Punjab, which today spans both India and Pakistan, was, therefore, the site of one of the earliest urban societies in the world.

And, as we’ll see, Punjab has seen plenty of history since then.

I. In Art

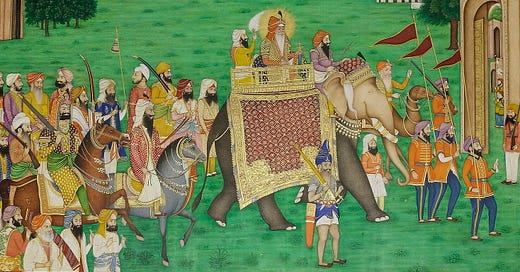

Ranjit Singh, or Sher-e-Punjab (“Lion of Punjab”), was the first Maharaja (Great King) of the Sikh Empire. After the decline of the Mughal Empire over the latter part of the 18th century, a power vacuum emerged in Punjab, which was eventually filled when Ranjit Singh unified the 12 misls (autonomous Sikh states), to create a single polity. At its greatest extent, the Sikh Empire stretched from Gilgit (northern Pakistan) and Tibet in the north to the Thar Desert in the south, and from the Khyber Pass (along the border of Afghanistan) in the west up to Oudh (bordering Nepal) in the east. The Sikh Empire would last up until 1849, when it was defeated and taken over by the British East India Company.

This painting was probably by a royal court painter of the Punjab rulers, and reflects the style of the Lahore School of Sikh painting. It’s hard to say exactly which Punjabi city makes up the background, if indeed it is supposed to be a true-to-life depiction of a real place at all, but the architecture shown has distinctly Islamic features, like iwans.

Sikhism originated in the Punjab region around the turn of the 15th century in the wake of spiritual teachings by Guru Nanak and the nine Sikh gurus that followed him. Today, Sikhism has some 25-30 million followers worldwide, the vast majority of which live in north-western India. The modern Indian state of Punjab is roughly 58% Sikh.

II. In Verse

“Today I implore Waris Shah to speak up from his grave and turn over a page of the Book of Love. When a daughter of the fabled Punjab wept he gave tongue to her silent grief. Today a million daughters weep but where is Waris Shah to give voice to their woes? Arise, O friend of the distressed! See the plight of your Punjab. Corpses He strewn in the pastures and the Chenab has turned crimson. Someone has poured poison into the waters of the five rivers and these waters are now irrigating the land with poison.“— excerpt from I Say unto Waris Shah, Amrita Pritam (1949)

Amrita Pritam was a poet, novelist, and essayist, and remains one of the most prominent figures in Punjabi literature. In this dirge, perhaps her most famous poem, she speaks directly to the great 18th century Punjabi Sufi poet, Waris Shah, to express her anguish over the ongoing violence and bloodshed in the wake of the Partition of India.

III. In Cartography

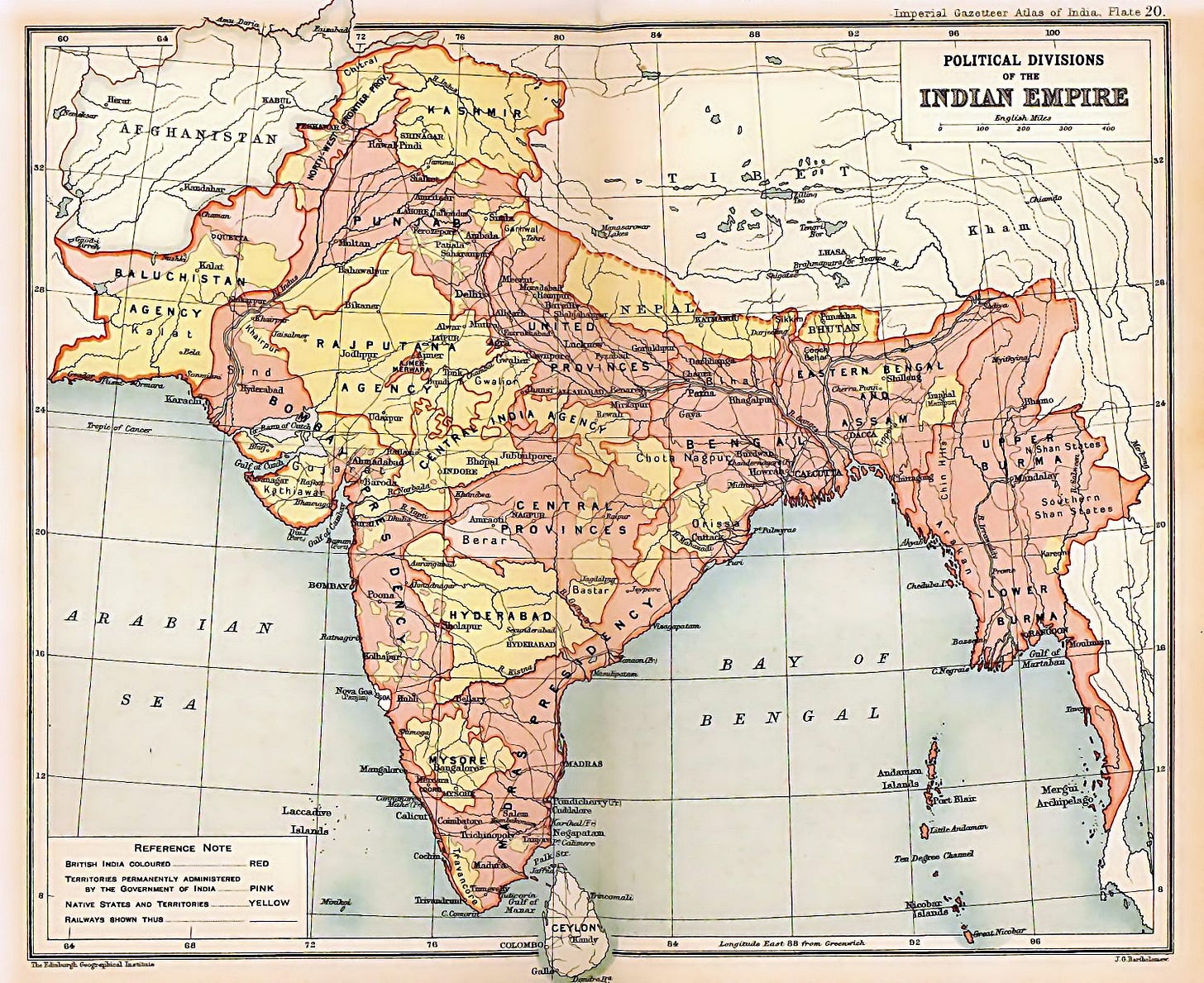

The above map shows the British Raj in 1909. The pink areas delineate British India —areas under direct British control— while the yellow show ‘Princely States’, or areas governed by indigenous rulers under British paramountcy. The cartographer, J. G. Bartholomew (who, incidentally, is credited with naming Antarctica), has chosen to label the colony ‘Indian Empire’ — an unofficial term that was sometimes used in place of British Raj.

We can see Punjab Province is a sort of butterfly shape in the northwest of the map. When the decision was taken to partition India into two independent states in 1947, Punjab was cleaved in two. West Punjab became a province in modern-day Pakistan, while East Punjab became a state in modern-day India (though now both just refer to themselves as “Punjab”, without a compass direction).

Many people living in the areas impacted by the Partition were scared and uncertain about the future. As the divide was intended to demarcate cultural/religious lines —a Muslim majority in Pakistan, and Hindu/Sikh majority in India— many feared finding themselves on the ‘wrong side’ of the border. In the period surrounding August 1947, it is estimated that over 15 million individuals migrated across the freshly drawn boundaries, an exodus marred by severe acts of violence. Punjab was the worst affected region, with the death toll estimated to be in the millions. (It was in the wake of this ongoing tragedy that Amrita Pritam wrote her poignant poem above.)

The map below shows the newly independent India just a few months after Partition. The many yellow areas show the autonomous states that still existed at this time. Hyderabad was annexed by India in 1948, Mysore (modern-day Karnataka) chose to join India in 1950, and Goa was annexed from the Portuguese in 1961. This map also still shows East Bengal as part of Pakistan — it became Bangladesh in 1971 after the Third Indo-Pakistan War. The large, most northerly yellow region on the map is Jammu and Kashmir, which of course remains in contentious dispute to this day.

IV. In Literature

“ततः पञ्चनथं चैव कृत्स्नं च कुरुजाङ्गलम तदा रॊहित कारण्यं मरु भूमिश च केवला अहिच छत्रं कालकूटं गङ्गाकूलं च भारत वारणा वाटधानं च यामुनश चैव पर्वतः एष थेशः सुविस्तीर्णः परभूतधनधान्यवान बभूव कौरवेयाणां बलेन सुसमाकुलः तत्र सैन्यं तदायुक्तं थथर्श स पुरॊहितः यः सपाञ्चालराजेन परेषितः कौरवान परति” “And for this reason the land of the five rivers (Panchanada), and the whole of the region called Kuru-jangala, and the forest of Rohitaka which was uniformly wild, and Ahichhatra and Kalakuta, and the banks of the Ganga, and Varana, and Vatadhana, and the hill tracts on the border of the Yamuna — the whole of this extensive tract — full of abundant corn and wealth, was entirely overspread with the army of the Kauravas.”— excerpt from Mahābhārata, Ved Vyasa (c. 3rd-4th centuries BC)

The Mahābhārata is one of two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India revered in Hinduism. It chronicles the Kurukshetra War — a war of succession between two groups of cousins.

As the story goes, the Pāṇḍavas, a group of five legendary brothers, ruled part of the Kuru Kingdom. The rest of the kingdom was ruled by their cousins, the Kauravas. However, one of the five, Yudhishtira, gambled away their share of the kingdom in a game of dice. According to the terms of the bet, the Pāṇḍavas had to hand over their portion of the kingdom and go into exile for thirteen years. On the Pāṇḍavas‘ return, the Kauravas refused to give back their portion of the land. Civil war ensued. Eventually, with the help of the god Krishna, the Pāṇḍavas won.

It is in the Mahābhārata that we find the first ever mention of Punjab, referred to as Panchanada, or “Land of the Five Rivers”, in Sanskrit. We can see in the text that the region was already well known for its fertile soil, and was said to have fought on the side of the Kauravas.

V. In Photography

“The world is a drama, staged in a dream.”

— Guru Nanak (the founder of Sikhism)

VI. Bonus Notes!

This is an experiment - a few bonus notes for paying subscribers. Let me know if you like this extra feature and I’ll think about making it a regular thing!