What if Columbus had never changed course?

What if he had landed at Florida?

Welcome to Cosmographia — a history of the earth and the stars. For the full map of posts, see here.

This is a bonus post on Columbus for paying subscribers. The next post will continue the story of Columbus’ first voyage.

Columbus first made landfall on the Bahaman island of Guanahani on 12th October 1492. But he could well have landed somewhere entirely different.

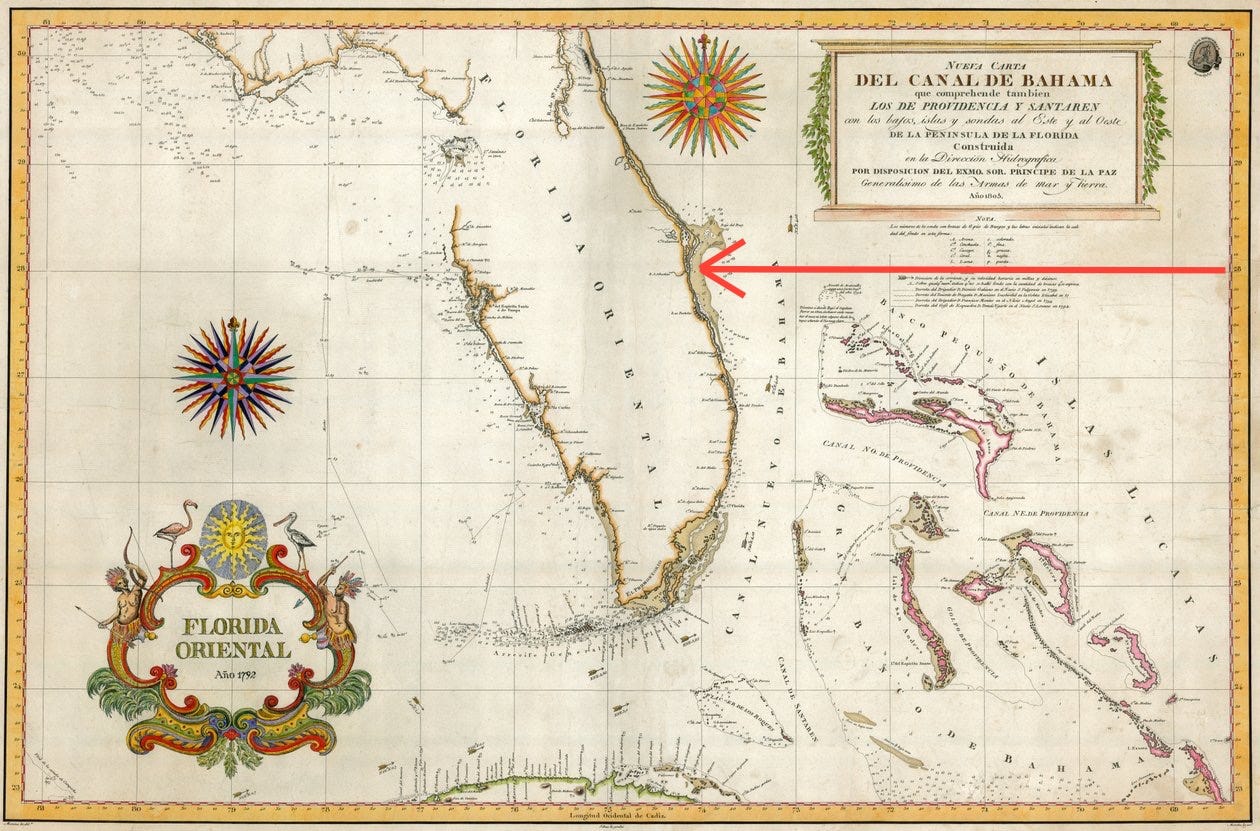

Armed with his fanciful calculations for the true size of the Earth, Columbus’ intention was to island-hop his way across the vast ocean sea to Asia. His study of the writings of Toscanelli, Marinus of Tyre, and Marco Polo led him to believe Cipangu (Japan) lay along the 28th parallel.1 To get there, he sailed south to the Canaries, which lies on that line of latitude, and then headed due west. He mostly kept to this line of reckoning for the first few weeks of his crossing, but as he neared the Americas he was persuaded by an unruly crew and birds flying overhead to change course and sail southwest, where he duly found the Bahamas. This led him on to Cuba and Hispaniola, which became the central nodes of the burgeoning Spanish Empire for the next century or so.

If however, he had stayed true to the 28th parallel, he would have landed not in the Caribbean, but on the Atlantic coast of Florida. If he had done so, I suspect the early decades of European contact with the Americas might have unfolded very differently.

Counterfactuals are often frowned upon by academic historians, but I’m a firm believer history should be fun. So let’s run with it: how would history have been different if Columbus had discovered mainland America?

Let’s imagine Columbus and his three ships landed on Florida, at approximately 28°N. This would have been roughly where the city of Melbourne, Florida, lies today. Here, the Europeans would have been greeted with a chain of barrier islands that enclose what is today called the Indian River. This is not a true river, but instead a system of three lagoons that shield the middle portion of mainland Florida from the open ocean. The eastern side of these islands and shifting sandbars would make for a dangerous anchorage, and with nothing sheltering the ships from the full force of the Atlantic Ocean behind, nudging them towards ever shallower waters, there would have been a real risk of getting stranded on a hidden sandbank, or wrecked entirely.

Unable to land, Columbus would likely have taken to sailing up and down the coast, no doubt concluding from the size of the landmass before him that he had found either the island Cipangu or mainland Cathay (China). As he proved in his navigation of the dangerous waters around the Bahamas, Columbus was a very adept sailor, so we can imagine he would have found and successfully navigated through an inlet into the calmer waters of the lagoon, where he and his men could at last lay anchor and visit the shore. Here, he would have found an abundance of marine and bird life (the Indian River is still today one of the most biodiverse places in North America); they would not have gone hungry. We can imagine him sailing up and down the lagoons, trying in vain to find any evidence of the riches of the East that Marco Polo had described in his Travels.

It’s been estimated that as many as 700,000 Native Americans lived upon the Florida peninsula at the moment of European contact, a density roughly equivalent to that Columbus found on the islands of the Caribbean. At this latitude, he would have met the Ais people, hunter-gatherers who subsisted on fish and shellfish. He would undoubtedly have pestered them for stories of gold. There was none. But if we imagine Columbus behaving as he did in the Caribbean, convincing himself that the signs and gestures of these strange peoples who he cannot understand are telling him precisely what he wants to hear: there are riches here about.

If I had to guess, I’d say Columbus would likely have chosen to explore northwards, rather than heading south. This is for a few reasons. First, the prevailing currents along the Atlantic coast of Florida tend northwards, drawn by the Gulf Stream in the northeasterly direction. If he was to allay the fears of his crews, who undoubtedly would have been worried about finding winds that could carry them home, heading north was the natural way to go.2 Second, Columbus believed Cathay to lie to the northwest of Cipangu, so if he was unsure if he had found the mainland, then he would have assumed it lay in that direction. Third, if he could glean anything at all from his conversations with the Ais fishermen, who would have had little in the way of resources to interest the rapacious Genoese, he might have learned that more sophisticated societies lived to their north. If he had headed south, waiting for him would only have been the impassable Everglades, sand-choked inlets, and little in the way of material wealth among the inhabitants.

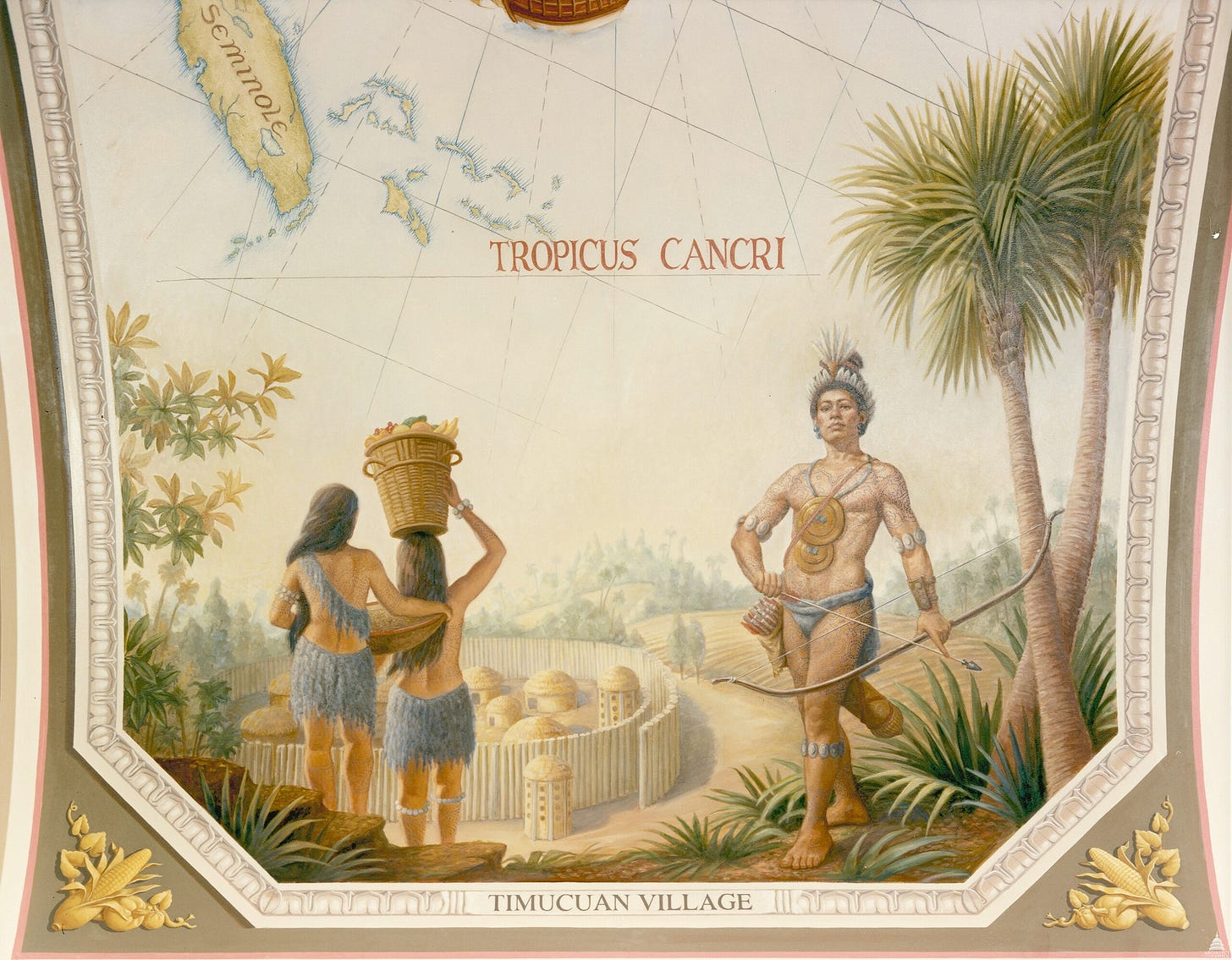

Not that that last point was much improved in the north. Here, Columbus would have found the Timucua people, a semi-agricultural culture divided among a constellation of approximately thirty-five different chiefdoms. They cultivated maize, beans, and squash, whilst also hunting animals like alligators, manatees, and fish. Again, they possessed little in the way of precious metals. No gold or silver to be found in northern Florida either.

If we imagine Columbus establishing a small settlement on his newly discovered lands, as he did on Hispaniola, then there are really only two candidate locations. The first that the Europeans would have encountered is at what is today the city of St Augustine, which was in fact the site of the first Spanish settlement on the peninsula (established in 1565). Here the relatively deep Matanzas River would have enabled good anchorage and an easy route back out to sea, while Anastasia Island would have provided shelter from Atlantic storms. The nearby Timucua village of Seloy would have enabled trade with an important chiefdom.

The second (and, in my opinion, better) location for a first settlement would have been on the site of what is today Jacksonville, straddling St John’s River. The French explorer René Goulaine de Laudonnière actually established the first European settlement in Florida here in 1564 (later torched by the Spanish), and it’s easy to see why. St John’s is the longest river on the peninsula and would have provided the perfect artery for further exploration inland. Columbus dispatched Luis de Torres into the interior of Cuba with a letter for the Great Khan of China — it’s easy to imagine him doing the same down St John’s. The river’s deep waters and easy access both inland and out to sea make Jacksonville a natural port. Drinking water and wood and stone for building were conveniently located nearby. Columbus did not have a great track record of identifying the best locations for new settlements, but for the sake of argument let’s assume this became the base for further Spanish expeditions.

After Columbus has explored a portion of Florida’s coast, and left a few men behind at a hastily built fort at Jacksonville (perhaps instead named Ferdinandville), I’d imagine his nagging crew would have forced him to set off home to Europe to tell all of what he’d found. I have no doubt he’d exaggerate the riches and splendour of his discoveries — that the great Kingdom of Cathay lay only a few leagues inland. Nevertheless, Florida would have made for a much tougher sell than the Antilles. The Spanish Crown was anxious for an immediate return on their investment. They needed concrete evidence that they would be able to make money from this venture. Florida would not have provided that.

While Columbus was able to return from the Caribbean with a small number of gold nuggets, which at least hinted at the possibility of an awaiting treasure trove, he’d have recovered nothing of the sort from Florida. The only resources he could actually return with would have been wood, coquina stone, salt, and perhaps the shells of sea turtles. None of these would have made for a remotely viable export economy. Despite this, I have faith that Columbus, ever the convincing salesman, would have secured backing for a second voyage, albeit one much smaller than that he embarked on in actuality.