Europe: Birth of History

The entire prehistory of Europe part IV

Welcome to Cosmographia — a newsletter dedicated to exploring the world and our place in it. For the full map of Cosmographia posts, see here. This is the part IV of the story of Europe’s prehistory; you can find part I here, part II here, and part III here.

…so that the actions of people shall not fade with time…

— Herodotus, on why he wrote his Histories (c. 5th century BC)

In our series on the prehistory of Europe, we have traced the human story on this continent through 400,000 years. We began with the age of the Neanderthals, when our closest human cousins still ruled Eurasia. We tracked our earliest forebears as they entered Europe for the first time, and saw how their descendants weathered the Last Glacial Maximum. After the world began to warm at the dawn of the Holocene, we watched as the practice of agriculture led to the building of mega-settlements and megaliths, before the Neolithic was swept aside by the mass migrations of steppe nomads from the East. All that remains left to do is tie the loose ends of our story into what came next: history.

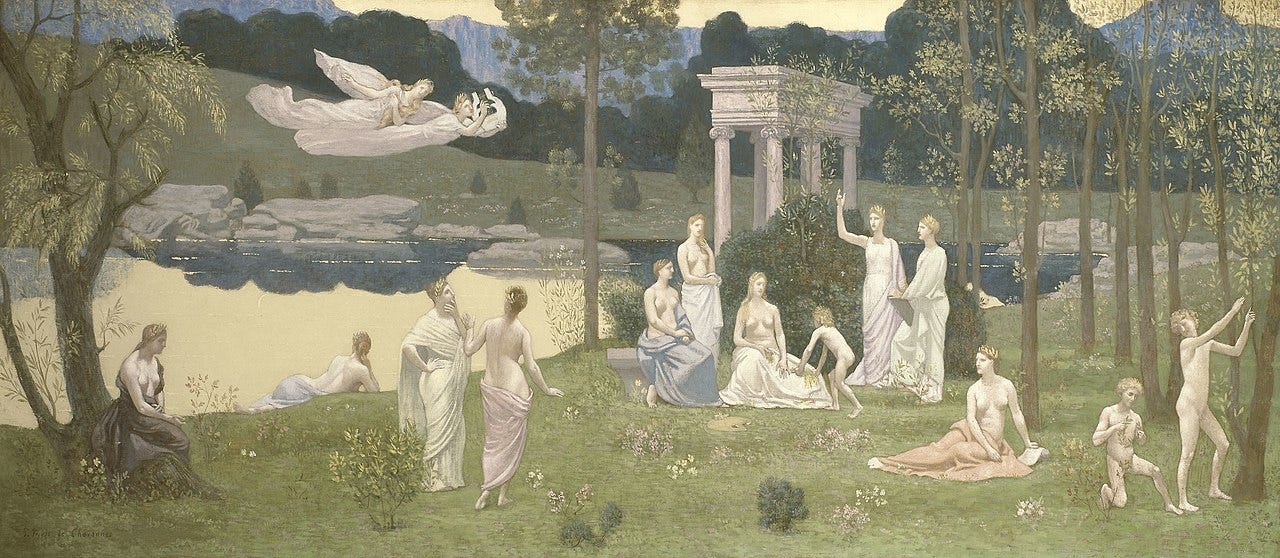

The first writing in Europe appeared on the island of Crete around 3800ya. The sophisticated Bronze Age civilisation that developed the Linear A script, as it’s known, built enormous palace-like complexes at Knossos and Phaistos, and traded goods all over the Eastern Mediterranean in the continent’s first sailing vessels. A millennium later, the Greeks mythologised the ruins of the long lost civilisation in the story of Minos — a despotic king who lured his enemies into a dark labyrinth, one stalked by a terrifying beast called the Minotaur. As such, the 19th-century archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans gave the Bronze Age people the name by which they’re now most commonly known: the Minoans.

Minoan writing has never been deciphered, so it’s not been possible to identify any linguistic clues as to where they might have come from. As such, historians have, until recently, only been able to speculate about their relation to the inventors of Linear B, the second European script.

The Mycenaean civilisation arose on mainland Greece ~1750 BC, seemingly stimulated by contact with the Minoans into forming a sophisticated culture of their own. Unlike their island neighbours, the Mycenaeans seem to have been rather warlike, building fortified towns and citadels. They take their name from their greatest city, Mycenae, which enters later Greek myth as the seat of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, heroes (and villains) of Homer’s two epics, The Iliad and The Odyssey. According to the poet, it was the King of Mycenae who led the Greek forces in their assault on Troy, only to be betrayed by his wife on his return home, a decade later. By the time Homer was writing his epics, the events of that ill-fated war were four centuries past, and the true deeds of the Mycenaeans, if they were involved at all, were long since lost.

What we do know is the Mycenaeans eventually expanded their influence across the Aegean to absorb the Minoan lands into their own. Their writing, the aforementioned Linear B, was deciphered in the 1950s, and was revealed to be an early form of Greek. Homer was right about one thing: the Mycenaeans of old were indeed Greeks.

Ancient DNA studies have revealed the Minoans descended primarily from the earliest farmers of the Neolithic (~75%), who crossed the Aegean from Anatolia to colonise Europe some 9000ya. Their remaining ancestry comes from further east, relating to ancient hunter-gatherer populations in the Caucasus and Iran — a mixture that surely must have occurred in eastern Anatolia before they crossed the Bosphorus. Mycenaeans look quite similar: they too are majority Anatolian Neolithic (~65%), with a smidge of the eastern ancestry mixed in. However, they differ in one respect — they have a small minority of genetic heritage stemming from the Pontic steppe region north of the Black Sea. At least in part, Agamemnon, lord of men, was descended from the Yamnaya.

Linguists have long known Greek to be an Indo-European language, and now we know its earliest form must have reached the Aegean via the movement of people, rather than cultural diffusion alone. The root of Europe’s earliest legible tongue stems back to the violent steppe pastoralist expansion of the continent’s prehistory; one can only speculate if the Mycenaeans’ fondness for war was inherited from their forebears in the same way.

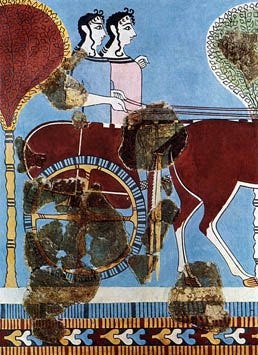

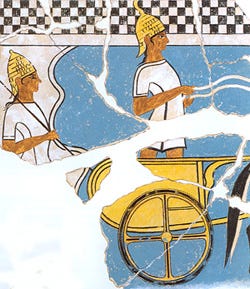

One thing we do now know: horses were domesticated on the Eurasian steppe around 5500ya. A millennium and a half later, the Sintasha culture, eastern descendants of the Yamnaya, invented the light war chariot, thus changing the landscape of ancient battlefields forever. By the 16th-century BC, the technology had reached Mycenaean Greece, where it was employed to great effect.1

A whirlwind cloud of dust rose to their chests, and their manes streamed in the wind. Now the chariots ran freely over the solid ground, now they leapt in the air, while the hearts of the charioteers beat fast as they strove for victory, and they shouted to their horses, flying along in the storm of dust.— Homer, The Iliad (c. 8th century BC)

Genetically, modern Greeks resemble the Mycenaeans, but with some additional dilution of the early Neolithic ancestry. As one paper puts it, the Aegean shows “continuity but not isolation” in the history of its people, from the Bronze Age right down to the modern day.

Virgil, the greatest of all the Roman poets, mythologised Rome’s origins in his epic, The Aeneid. Aeneas, Prince of Troy — so the story goes — fled the burning city as it fell to the Greeks, arriving after a journey to rival that of Odysseus in Central Italy, where he began the line of kings that would end with those ill-fated brothers, Romulus and Remus. It is of course a fanciful story, designed to reinforce the Romans’ belief that they were a special people with a storied heritage. But, in fact, there is more truth to it than one might expect. The Romans could trace some of their ancestry back to Anatolia after all.