Network of Letters

Cartography of Networks: Edition VI

Welcome to Cosmographia. This post is part of our Cartography of Networks series. For the full map of posts, see here.

If there is something you know, communicate it. If there is something you don’t know, search for it.

— Encyclopédie (1772)

The Age of Reason, also known as the Enlightenment, was a revolution in thought that emerged in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. The revolution encompassed many fields — politics, science, and philosophy — and saw for the first time in a long time the championing of human reason as the central means for understanding the world and our place in it.

The Enlightenment had its origins in the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, when the strict doctrines of the Catholic Church were openly questioned and its authority began to diminish. The name comes from the idea of emerging from the ‘darkness’ of the Middle Ages, which as we’ve seen wasn’t quite as dark as ordinarily portrayed. Regardless, the Enlightenment can still be seen as a hinge moment in the history of ideas, where deference to authority, superstition, and unquestioning obeisance to tradition came under increasing challenge.

Of course, this emphasis on reason didn’t arrive out of nowhere: the Enlightenment was greatly influenced by thinkers of the previous century. Francis Bacon (1561-1626) put great emphasis on testing knowledge through empirical experimentation; Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) proposed his idea of a ‘nasty, brutish, and short’ life in the state of nature, and thus opened up questions about the social contract citizens make with each other to elevate themselves above that state; René Descartes (1596-1650) proposed all knowledge should be subject to doubt, and thinking must start from first principles (cogito, ergo sum); Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) attacked superstition and advocated for reason in understanding the world and the divine; John Locke (1632-1704) proposed ideas about relationship between the individual and the state, opening up questions of political philosophy and the rights of citizens.

Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687) is often seen as both the culmination of the Scientific Revolution and the beginning of the Enlightenment. His book, which outlined Newton’s laws of motion and the law of gravitation, was not only one of the most important works in the history of science, but also showed that the world can be understood in material terms through mathematics. Newton’s tools of empiricism and deduction were soon adopted in other fields.

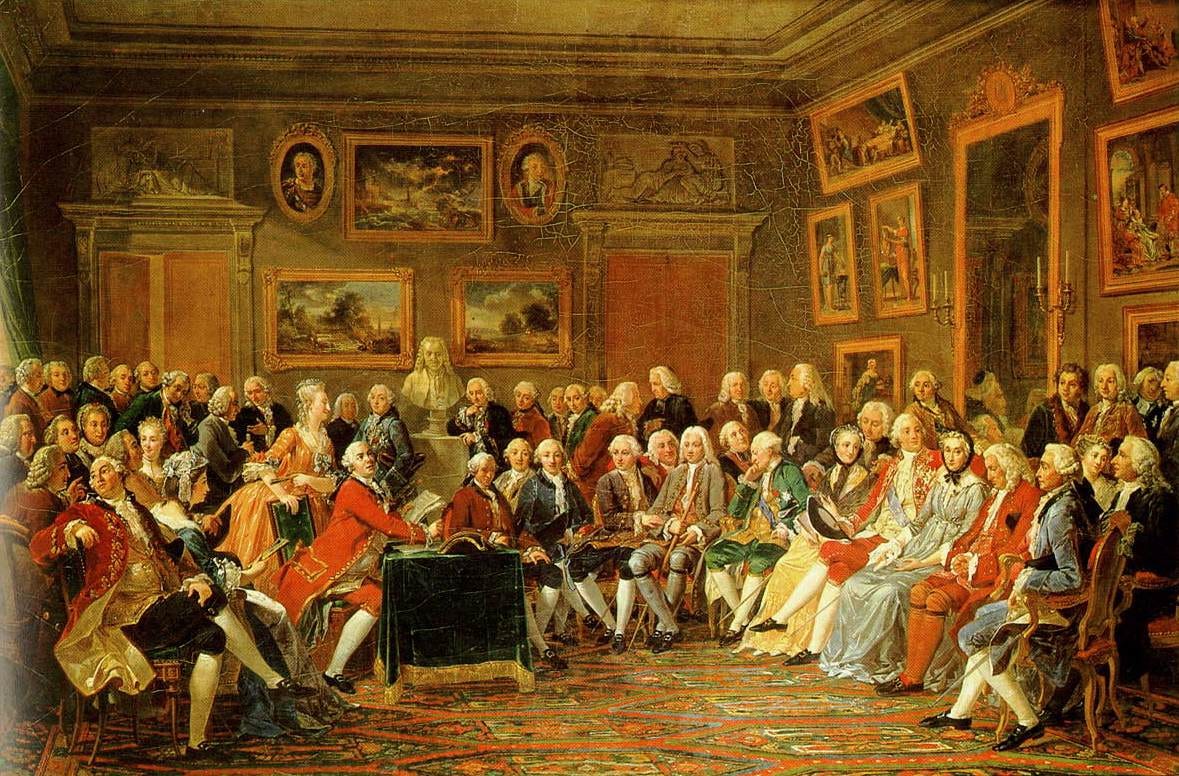

The Enlightenment found perhaps its greatest footing in France. The philosophe Montesquieu (1689-1757) built on the work of Locke by reviewing the entire history of politics, founding political science in the process, and argued for the separation of powers between the executive, legislative, and judiciary for the first time. Meanwhile, Denis Diderot (1713-1784) was a great proponent of individual autonomy and the subjection of all knowledge, especially tradition, to scientific arguments and methods. But the man who personified the French Enlightenment more than any other was Voltaire (1694-1778). The author was a lacerating critic and one of history’s great satirists, leaving in his wake a trail of destruction of old attitudes. He demanded more individual liberty and religious tolerance, and was a particularly vocal critic of the Catholic Church’s power. He was perhaps the Enlightenment’s greatest champion of human reason.

The Enlightenment also took root in Scotland. David Hume (1711-1776) presented an empiricist philosophy that made the case that knowledge comes from experience and observation, while Adam Smith (1723-1790) founded economics as a science and outlined his concept of the ‘Invisible Hand’ guiding the complex interactions of commerce.1

Further south, the Anglo-Irish Edmund Burke (1729-1797) pushed back slightly on the progressivism of some of his peers, making the case for Enlightened conservatism and the importance in not throwing out institutions (including religious ones) that have long guarded social stability and individual liberty. His fellow countryman, Thomas Paine (1737-1809), took a different view in his pamphlet Common Sense when he called for the American colonies to throw off the yoke of British rule and taxation. He was a fierce critic of slavery and believed firmly that all men are equal and should have the right to vote.

Back on the continent, the intellectual giant Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) took an anti-Hobbesian view of political philosophy, proposing instead a much more egalitarian view of the state of nature. In The Social Contract (1762), Rousseau outlined his ideas around the need for consent to legitimise political authority, openly criticising the divine right of monarchal government. Meanwhile in Königsberg, Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) pushed back on the dominance of empiricism and rationalism in Enlightenment thinking, making the case for a priori knowledge — understanding that comes without direct experience. He also made great contributions to ethics, arguing that moral value comes from intentions, not consequences — a view opposite to the English utilitarianist Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832).

The Enlightenment also saw the strictures that had traditionally governed the role of women in society come under increasing challenge. Catharine Macaulay (1731-1791) and Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) both argued for the education of women, making the case that unleashing the intellectual capacity of half of the population would only accelerate progress. The French playwright Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793) went further, arguing for the political rights of women to match those of men.

These thinkers, only a fraction of the total, formed the primary ‘nodes’ of the intellectual network that was revolutionising European thought in the 18th century. But what of the edges between them?