Why did humans first build cities?

Welcome to Cosmographia — a newsletter dedicated to exploring the world and our place in it. For the full map of posts, see here.

This is the first in a short series of posts about the origins of urban development.

Cities are the engines of human civilisation. They are the forges of new technology; the batteries that power our economies; the high seats of political power; and the birthplace of humanity’s greatest achievements in art, literature, and music.

But for most of human history — some ~294,000 years — we did not build cities. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors lived in small bands of no more than 150 people, sometimes with an egalitarian social structure, other times not. Many were nomadic, roaming across their territories to follow the seasonal migrations of their prey, to fish in local waters, to use their intricate knowledge of their environment to find fruits, tubers, and nuts as they ripened. Where nature’s bounty was especially abundant — like say, the Pacific Northwest, where the salmon migrated in such numbers as to provide the local communities enough food to last all year — foragers were sedentary. Some hunter-gatherers even built small settlements: the mammoth-hunting Gravettian people built clusters of huts from their prey’s bones and pelts as early as 22,000 years ago.

But, if some of our ancestors were able to live sedentary lives, and even build small villages, why do cities appear so late in the human story?

The common answer to this question is a simple one: urban development was only made possible with the invention of agriculture 12,000 years ago, after the world had sufficiently warmed after the end of the last ice age. The food surplus provided by abandoning the forest in favour of the fields, so the argument goes, led to the necessary population growth required for new forms of social organisation. Thus, humans were able to form groups larger than the limit of Dunbar’s number for the first time.1 Agricultural communities built villages near their farms; over time these villages became towns, and, eventually, towns because cities.

But this argument is incomplete. Agriculturally induced population growth was almost certainly necessary for urbanisation, but it was not in itself sufficient.2 This becomes clear as soon as you consider the fact that cities arose only in a few places. Agriculture spread from the Near East into Europe around 6000 years ago, eventually reaching the shores of the Atlantic another millennium later. Why then, does the first city in Western Europe not appear until 1100 BCE? Even that settlement, Cádiz, Spain, did not emerge spontaneously, but was founded by colonists from the city states of Phoenicia. The black-earth steppes of Ukraine are famously among the most fertile plains in the world, yet they didn’t seed a true city until the 4th century BCE — another colony, founded this time by Greeks.

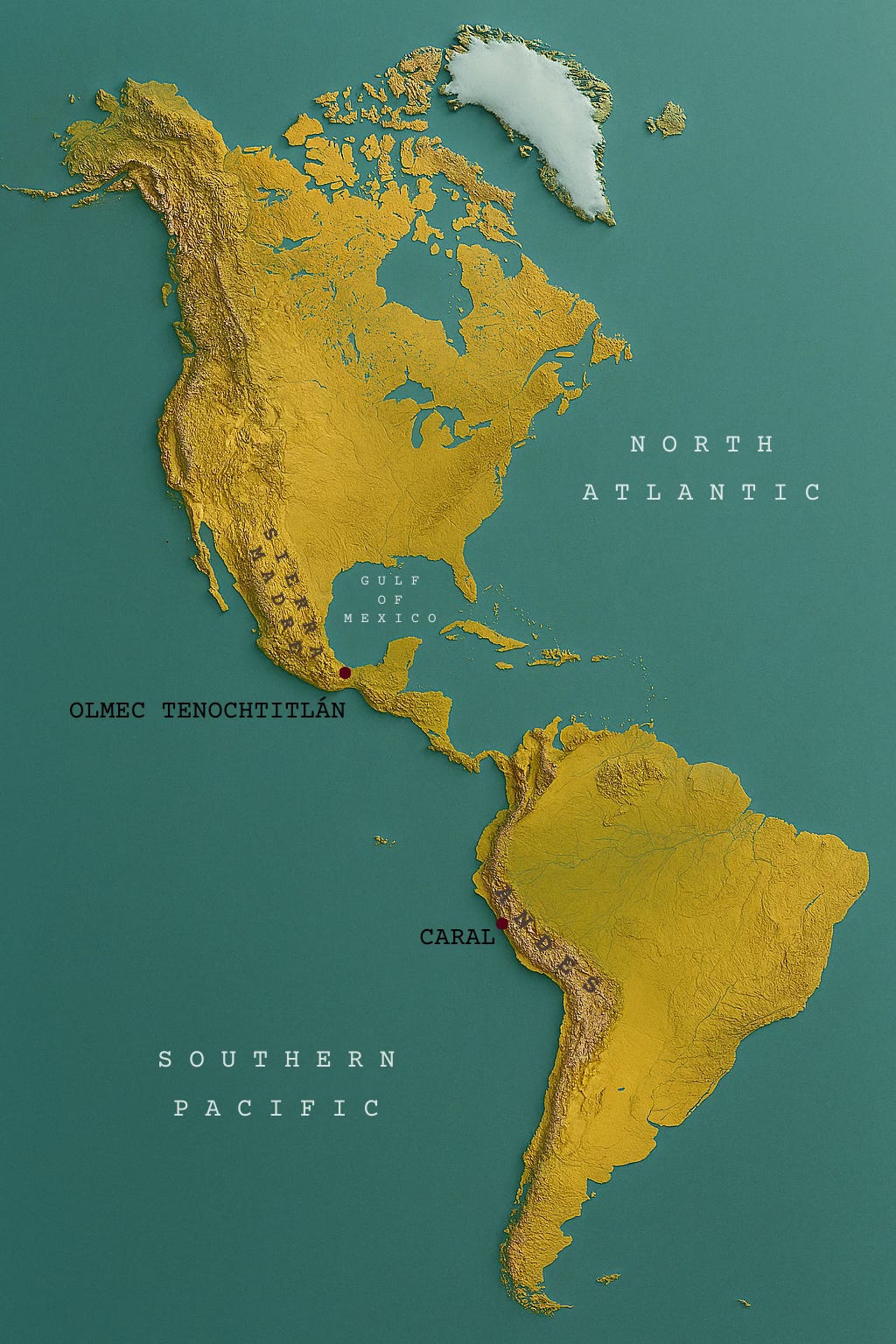

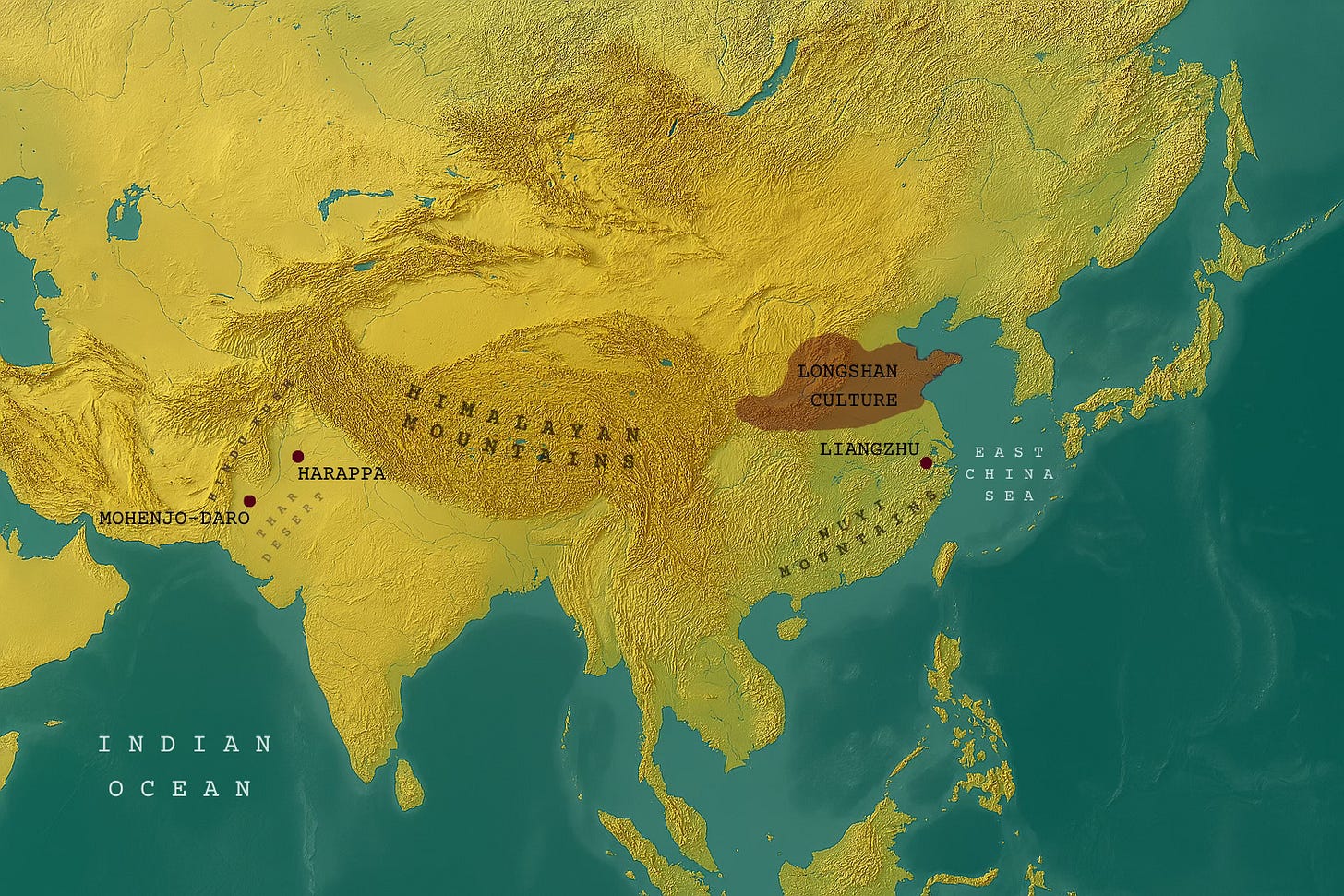

Most cities that exist in the world today came to be founded by some process of cultural diffusion. Their founders had other urban centres to copy. But — by definition — the first cities in each of the six original centres of ancient civilisation — Mesopotamia, the Nile Valley, Peru, the Indus River Valley, the Yellow River Valley, and Mesoamerica — had no one to imitate. In startup-speak, they had to go from zero to one.

But why in those places, and not others? What was special about them? What was it that caused the first urbanites to break with hundreds of thousands of years of tradition? Why did humans first build cities?

When one compares the sites of the earliest urban centres, at first they seem to have little in common. They had different climates, different soil types, and different local ecologies. Their inhabitants grew different crops — wheat and barley in Mesopotamia, rice in China, maize in Peru — and cultivated their fields in different ways; some used paddies, others complex irrigation networks, while still others relied on an annual flood of their local river.

But they did all share one important feature: they were each founded in oases of fertile land, which were themselves surrounded by harsh environments. In other words, they were environmentally circumscribed.

Take the case of the first urban centres of the Near East, for example. The earliest cities in Southern Mesopotamia, Uruk and Eridu, were built near the Euphrates River amid marshes and irrigable flatlands. However, this agriculturally productive land was hemmed in by the Arabian desert to its west, the Persian Gulf to its south, and the Zagros Mountains to its north and east. The limited alluvium seems to have forced the local population, already swelled by improving agriculture, into a density hitherto unknown. The geography compressed people into a limited territory, and like carbon squeezed into a diamond, they became something new: a complex society.

In Egypt meanwhile, the Nile Valley provided a narrow ribbon of fertile floodplain in an otherwise inhospitable desert. Long before the Old Kingdom rose its sphinxian head, the desert had already forced early Egyptians to densify along the riverbanks. The first African urban centres formed at Hierakonpolis, Naqada, and Abydos, within the limits of river’s annual flood — beyond which no rain-fed agriculture was possible. Even today, 95% of Egypt’s population lives within a few miles of the Nile.

It was a similar story in the Americas. The principal city of the Norte Chico civilisation (c. 3500-1800 BCE), Caral, was located in a narrow valley in the Andean highlands. This arid plain was bounded by two rain shadows (caused by the peaks of the Andes and trade winds in the Pacific), but was made fertile by extensive irrigation — in a similar fashion to the more arid parts of Mesopotamia. Along the more expansive coast, where the farmable plains were less bounded, urban development didn’t arise in the same way.

Further north, the Olmec civilisation (1200-400 BCE) flourished much later in the Gulf lowlands of Mexico. Their first urban centre, San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, formed in an agriculturally bountiful region hemmed in by a spine of the Sierra Madre mountains to its west, the Tuxtla Mountains and Gulf of Mexico to its north, and swampland to its east. The city itself was built atop a small plateau that rose 50m above the floodplain of the nearby Coatzacoalcos River — a circumscription in miniature.

In South Asia, the Indus Valley Civilisation (c. 3300-1300 BCE) spanned a broad alluvial plain, but this fertile area was also encased by formidable geographical barriers. To the east of the early cities of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa lay the wastes of the Thar Desert, to their west lay the Hindu Kush mountains, while the Himalayas rose forbiddingly to their north.

In China, the first true city appeared at Liangzhu (c. 3300-2300 BCE), located in a riverine plain bound on three sides by branches of the Tianmu Mountains. To Liangzhu’s north, the sprawling Longshan culture provides a case study in itself of urban development. Centres appeared in the environmentally circumscribed regions of the Fen River basin, the lands in western Henan bounded by the Zhongtiao and Xiao Mountains, and the coastal plain of southeast Shandong. The more open areas of the Yellow River basin, meanwhile, saw no such urbanisation.

The importance of environmental circumscription can be seen too in those places where settlements seemed on the verge of urbanisation, but never quite made it.

Take for example, Göbleki Tepe, a Pre-Pottery Neolithic settlement that was inhabited (on either a permanent, or semi-sedentary basis) for roughly a millennium, beginning some 11,500 years ago. Despite initial theories that the site was a ritual centre built by hunter-gatherers, recent investigations suggest instead that this monumental complex is one of the earliest agricultural villages yet discovered. Given Göbleki Tepe was built so soon after the dawn of the Holocene (our current geological epoch, when the climate began to get warmer and wetter), it seems its founders’ were able to densify incredibly quickly in the new environmental conditions. It’s wondered if the depleted populations of prey animals after the Younger Dryas event (a period of snap cooling ~12,900-11,700 years ago) may have caused early farmers like the builders of Göbleki Tepe to begin cultivating and processing wild grains, in the absence of other food sources. If that’s true, then it was the environmental conditions, rather than agricultural surplus, that caused them to group together in greater numbers.

So why then, wasn’t Göbleki Tepe able to fully urbanise into a city? A clue can be found in its geography: the site lies at the northern edge of the Fertile Crescent, on a rise overlooking the Harran plain. Though the immediate environment is fairly arid, the Tepe-builders managed to construct a complex cistern system to catch and store rainwater — a technology that could have been copied and taken elsewhere in the region. Being located as it was near to a great belt of fertile land, the local geography did not compress the population together as it did in the places full urbanisation occurred.

It was a similar story at Çatalhöyük (c. 7500-5600 BCE), a much larger Neolithic settlement in southern Anatolia. Here a collection of mud-brick houses were built alongside one another in an aggregate structure resembling a honeycomb. Composed entirely of houses, with no public or communal spaces, the town had no streets — its inhabitants reached their home via ladders and beams stretched across the roofs of its buildings. Despite its thousands of residents (at its peak anywhere from 3500-8000 people), Çatalhöyük never evolved from what was essentially a large village into a city, its population eventually dispersing into a series of smaller farming hamlets. Why? The site lay on the Konya Plain, a broad flat basin covered in a bountiful wetland, replete with fish, water birds and their eggs, prey animals, and farmable fields that were flooded by the river every year. Crucially, beyond the immediate wetlands, the Konya Plain offered plenty of space for new settlements, and over time people did spread out.

Further north, the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture (c. 5000-2700 BCE) spanned western Ukraine, Moldova, and eastern Romania for over two thousand years. Most of their settlements were of a small size — villages spaced roughly three to four kilometres apart. However, in a few places, the Cucuteni-Trypillia built ‘mega-sites’ of a few thousand buildings, which potentially housed tens of thousands of inhabitants. Though their material remains show elaborately decorated pottery, sophisticated metal working of copper and gold, and fairly advanced architecture in the form of large log homes (as well as wattle-and-daub and semi-underground houses), their mega-sites never developed into true cities either.3

Again, this inability to urbanise when seemingly so close to doing so can be explained by the local geography. The Cucuteni-Trypillia culture extended from the Carpathian Mountains all the way across to the lush basins of the Dniester and Dnieper rivers in Ukraine. This territory marks the beginning of the Pontic Steppe, an extremely fertile region that itself forms part of the Great Eurasian Steppe — the largest temperate grassland ecosystem in the world. In other words, the inhabitants of the Cucuteni-Trypillia could not have been less constrained by their environment. At any given moment, they could have upped sticks and moved on without having to worry about where they’d find new pastures.

For the residents of Göbleki Tepe, Çatalhöyük, and the mega-sites of the Cucuteni-Trypillia, the relatively open geographies in their immediate environment acted as a release valve for population pressure, preventing full-scale urbanisation.

It seems then, the world’s first urbanites became so not only because of agricultural surplus, as the old narrative goes, but at least in part because of geography too. The first known cities in each of the six centres of ancient civilisation all blossomed in fertile pockets sharply delimited by deserts, mountains, or seas. Such environments acted as a cultural pressure cooker, increasing population density and interactions between groups, until they birthed something new: the city.

We should think of the natural environment as exerting a selection pressure not just on our biology, but on our culture too. Cities are if nothing else a social technology — one far more novel than we often care to remember — but one as influenced by the local environment as the practice of agriculture.

This doesn’t mean that geography is necessarily destiny — there appears to have been a few ecologically pressed regions that never gave birth to cities (places like the Pacific Northwest and the highland valleys of Papua New Guinea). Perhaps, like agriculture, environmental circumscription was necessary for urban development, but not sufficient.

Regardless, there’s no denying there’s a strong correlation between circumscription and urbanisation. It’s even been suggested that perhaps it’s no coincidence that the most environmentally circumscribed region of them all — the Nile Valley — saw the longest surviving of the ancient civilisations. Though dynasties came and went, there was invariably some form of state, and with it cities, clinging to the riverbanks. The strip of inhabitable land was so narrow that people were forced to work together no matter what calamities befell them. Perhaps the geographical pressures were so strong they held together what would otherwise have become a fallen state.

The next few posts in this mini-series on the origins of cities will include:

- The evolutionary pre-adaptions that made human beings suitable for urban life

- What social structures emerged in the first cities?

- The importance of ‘god-kings’ in early urban development

Dunbar’s number being the suggested cognitive limit of the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships — normally believed to be around 150.

Another problem with this narrative is that it presumes that the invention of agriculture was a single, momentous change in human history. This is not true. Humans were processing wild grains as early as 22,000 years ago, while the last ice age still raged, and many groups began and then abandoned the intentional cultivation of plants multiple times. Like many human innovations, the adoption of agriculture was a slow and gradual process.

There are some who would claim that the Cucuteni-Trypillia mega-sites do in fact qualify as cities. This gets us into an argument about definitions, but I’d suggest that urbanism isn’t construed by scale alone. Instead, a city is best defined by things like social stratification, public architecture, monumental infrastructure, administration, complex economics and specialisation, and bureaucracy. These sites had little to none of these, and that’s without mentioning the fact they were only inhabited for sixty to eighty years before undergoing some form of ritualistic burning.

Notes

Carneiro, Robert L. (1970). “Theory of the Origin of the State”, Science

Frankopan, Peter (2023). The Earth Transformed.

Fascinating topic, isn't it? I was curious to see if you'd mention Çatalhöyük because I have an as-of-yet unpublished novel that partly takes place there!

Funny, I've always been fascinated by the origins of civilization but never really thought about the role of geography in terms of forcing people together in a relatively small area of arable land. My daughter has been studying this period in school, and now I'm excited to tell her about that particular wrinkle. (She will likely roll her eyes at me, which is only to be expected.)